Placed by: LDS 38th North Ward Priests[1]

GPS Coordinates: 40° 45’5.76″N, 111° 48’3.28″W

Historical Marker Text:

Lured by Lansford Hasting’s assurance that his shortcut from the well-known trail to Oregon and California would save 250 miles and weeks of travel, the ill-fated Donner-Reed party reached this place August 23, 1846, after spending 16 days to hack out a 36-mile road through the Wasatch Mountains. Here at this narrow mouth of the canyon, they were stopped by what seemed impenetrable brush and boulders. Bone-weary of that kind of labor, they decided instead to goad the oxen to climb the hill in front of you. Twelve-year-old Virginia Reed, later recalled that nearly every yoke of oxen was required to pull each of the party’s twenty-three wagons up the hill. After this ordeal, the oxen needed rest, but there was no time. The party pushed on to the Salt Flats, where many of the oxen gave out. This caused delays, which led to disaster in the Sierra Mountains.

A year later, July 22, 1847, Brigham Young’s Pioneer Party, following the Donners and benefitting from their labor, reached this spot. William Clayton recorded their decision: “We found the road crossing the creek again to the south and then ascending a very steep, high hill. It is so very steep as to be almost impossible for heavy wagons to ascend…Colonel Markham and another man went over the hill and returned up the canyon to see if a road cannot be cut through and avoid this hill. Brother Markham says a good road can soon be made through the bushes some ten or fifteen rods. A number of men went to work immediately to make the road…After spending about four hours of labor the brethren succeeded in cutting a pretty good road along the creek and the wagons proceeded on.”

Among the lesson learned that day was one stated succinctly by Virginia Reed in a letter to prospective emigrants back home: “Hurry along as fast as you can, and never take no shortcuts.”

Extended Research:

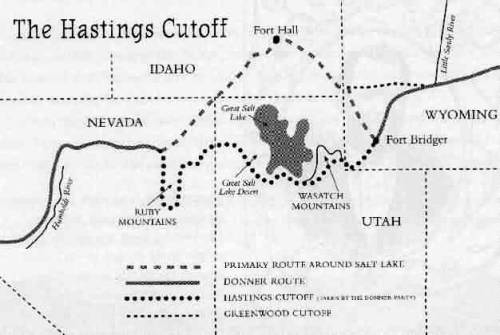

In 1846 a wagon party led by George Donner departed Independence, Missouri and began a perilous journey from the United States towards Alta California in Mexico. The wagons were late in reaching the Sierra Nevada mountain range and disaster awaited the 88 members of the Donner Party. Extreme suffering and starvation followed, with 41 members of the group dying and eventually the incident drew national attention over reports that some members of the ill-fated party resorted to cannibalism in order to survive.[2] The Donner Party originally planned to travel to California via Oregon, but real estate speculator Lansford Hastings promoted an alternate route published in his famous Emigrants Guide to Oregon and California in 1845, and the Donner Party opted to try it.³

Hastings was not certain if he should promote the cutoff from Fort Bridger through the Salt Lake Valley and westward following John C. Fremont’s expedition in 1845, but he received support in favor of the cutoff from Fremont and Jim Bridger. Hastings thus advised the Donner-Reed party that they would save some 350-400 miles if they took his “cutoff.” One of his partners, James Clyman, however became convinced that the route was not suited for wagons and therefore tried to dissuade members of Donner-Reed Party from taking the cutoff. Joseph R. Walker, who successfully guided the first wagons over the California Trail by way of Fort Hall, also thought the route an unproven risk.[3]

Other migrant groups, which included the Bryant-Russell Party and Harlan-Young wagons, left Fort Bridger in mid-July 1848, following the Bear River into East Canyon where they passed through Devil’s Gate with difficulty along the Weber River. Hastings subsequently directed a group of German migrants from the Heinrich Lienhard party on a direct route through Echo Canyon into Devil’s Gate, where they caught up with the Harlan-Young party near the Jordan River. The Donner Party departed Fort Bridger two weeks later on July 31 and Hastings talked them out of going via Weber Canyon and Devil’s Gate, instead telling them to blaze a new path over to what would come to be called Emigration Canyon. On August 7, 1846, James Reed began carving a trail for the wagon train, chopping down bushes and trees in the Wasatch Mountains towards the canyon. Reed was joined by the remaining members of the wagon party who continued to hack and dig their way for 35 miles from present-day Henefer, Summit County, to Salt Lake City.²

The Bryant-Russell, Harlan-Young and Lienhard parties would successfully pass through the Sierra Nevada Mountains into California, while the time the Donner Party spent trailblazing in Utah foreshadowed later events. After the three week trek through the Wasatch Mountains, the oxen were already exhausted and their supplies began to run low.

After entering the Salt Lake Valley, the first member of the party died of tuberculosis near the Great Salt Lake. A site near Grantsville, Utah provided temporary relief with underground water springs, their last source of water until reaching the Humboldt River. In the Salt Flats, Reed’s thirsty oxen ran off and were never seen again. Upon reaching Iron Hill, a fight broke out between one of Reed’s teamsters and John Snyder, a driver for the Graves wagon. Reed stabbed Snyder in the chest and was banished by the Donners after Snyder died. Reed thus avoided being pinned down by the early winter storms which trapped the rest of the party. His departure in October towards Sutter’s Fort allowed him to organize a rescue party in Sacramento that arrived in February 1847. Along the Humboldt River a band of Paiute Indians killed 21 of the Donner Party’s oxen and stole another 18, with more than 100 of the party’s cattle now gone. Two Indian guides assisted the Donner Party in reaching the summit of the Sierra Nevada, but turned back with the first sign of snowfall in early November.1

The delayed timing and trek through the west desert led to the party becoming snowbound in the Sierras. Malnutrition was a common cause of death, and Irish immigrant Patrick Breen wrote in his journal on Christmas Eve that he was living in a “Camp of Death”. 1 Some of the members of the party camped along the banks of Alder Creek and frozen Truckee Lake, now Donner Lake, where most of the cannibalism occurred. The first rescuers arrived at Truckee Lake in February 1847, composed of soldiers from the U.S. Army stationed in California during the U.S.-Mexican War, among them were members of the Mormon Battalion. One week after rescuers arrived, other isolated camp sites were still using the corpses of the dead for food. Breen wrote in his diary on February 26:

Martha’s jaw swelled with the toothache: hungry times in camp; plenty hides, but the folks will not eat them. We eat them with a tolerable good apetite. Thanks be to Almighty God. Amen. Mrs Murphy said here yesterday that [she] thought she would Commence on Milt. & eat him. I don’t [think] that she has done so yet; it is distressing. The Donners, 4 days ago, told the California folks that they[would] commence to eat the dead people if they did not succeed, that day or next, in finding their cattle.1

Three additional relief efforts occurred in April in an attempt to find members who had become separated while camping along Truckee Lake. In the last effort they found only one survivor, Louis Keesberg, who was surrounded by half-eaten corpses. As the survivors departed with the rescuers, members of the Mormon Battalion were ordered to bury the dead bodies inside the main cabin on what is today Donner Pass and then set fire to the cabin.[4]

The Donner Party, in essence, blazed the trail into the Salt Lake Valley which Brigham Young and the Mormon Pioneers used the following year. Young left Winter Quarters, Nebraska with his encampment and passed through the mouth of Echo Canyon by mid-July 1847; he then picked up the Donner-Reed trail and followed it into the Salt Lake Valley. Instead of three weeks, it took Young’s party one week, a matter of great importance since it enabled the Mormons to plant wheat and potato crops in time for their first harvest in the fall. In the last quarter-mile, rather than hauling their wagons over Donner Hill, the Mormons decided to hack through the brush and go around Donner Hill. The Mormons emerged four hours later at what is now This is the Place State Park.[5]

For Further Reference:

Primary Sources:

Breen, Patrick. Diary of Patrick Breen of the Donner Party, 1846-7. Berkeley: University of California Bancroft Library, 1910.

Secondary Sources:

Campbell, Eugene. “The Mormons and the Donner Party.” BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 11 no. 3 (1971).

Miller,

David. “The Donner Road through the Great Salt Lake Desert.” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 27, no. 1 (February 1958): 39-44

[1] Originally installed by “Mormon Explorers” Y.M.M.I.A. In 2010, the original plaque was stolen and re-erected in 2016 by the LDS 38th North Ward High Priests

[2] Campbell, “The Mormons and the Donner Party.”

[3] Miller, “The Donner Road through the Great Salt Lake Desert,” 39-44

1 Breen, 18

1 Breen, 28

[5] Campbell, “The Mormons and the Donner Party.”