Write-up by: Krystan Morrison

Placed by: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, No. 53

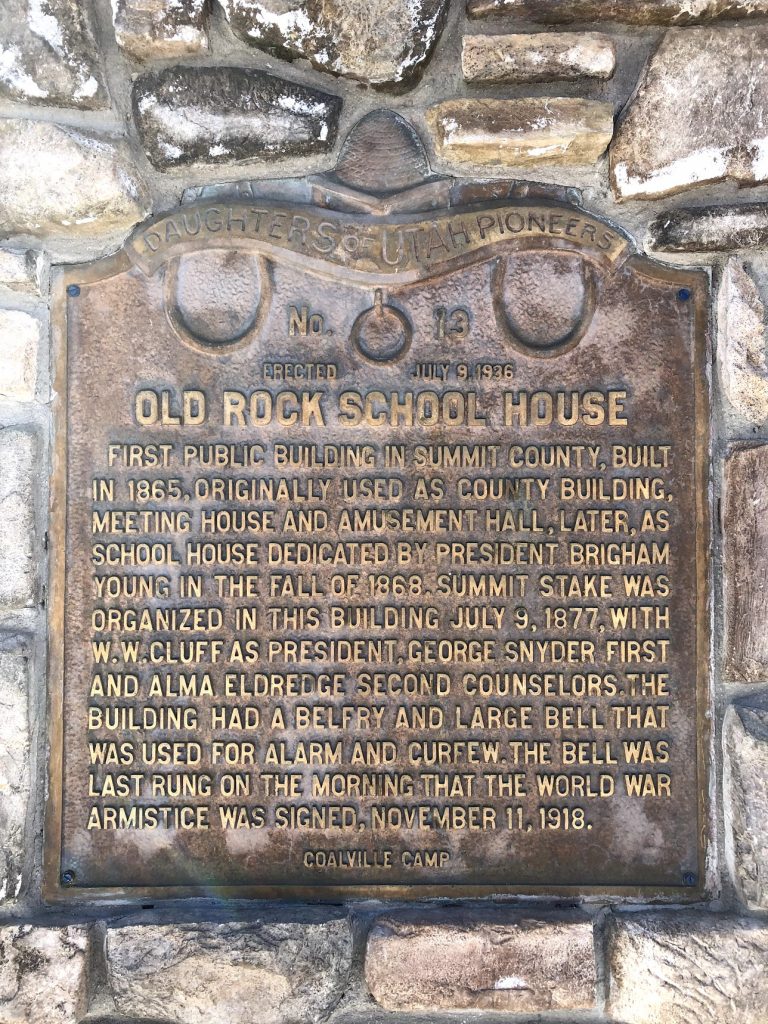

Historical Marker Text:

“Daughters of the Utah Pioneers

No. 53

Erected Oct. 15, 1933

First University West of the Mississippi

The parent school of the University of Deseret, established November 11, 1850 in the home of John Pack, was located on this corner. Forty students enrolled the first year. Produce, lumber, etc. were taken for tuition and sold by Mr. Pack. Cyrus W. Collins was the first teacher. In 1851 the school was moved to the council house, then to 13th ward hall, in 1867 back to the council house, 1876 to the union square 2nd west & 1st north streets. In 1892 the name was changed to University of Utah and in Sept. 1900 moved to the present site.

Camp 17 Salt Lake County”

Extended Research:

Not long after their arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, LDS church leaders and community members were eager to establish an educational institution that upheld and promoted the values of Latter-day Saints. On February 28, 1850, these hopes became a reality when an act passed by the General Assembly of the State of the Deseret (only one month after the assembly originally convened) created a school that came to be known as University of the Deseret.[1]

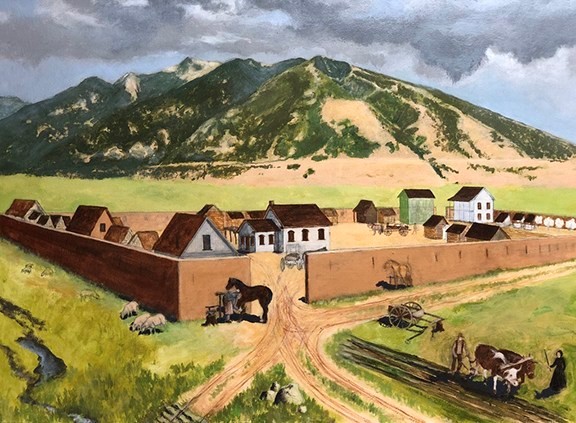

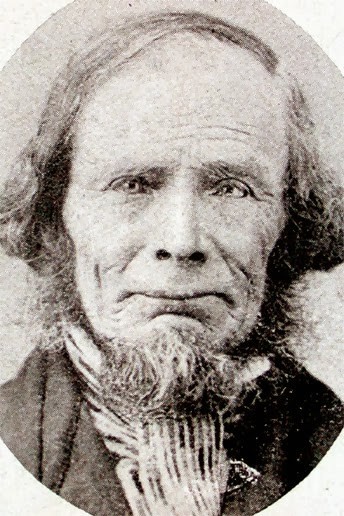

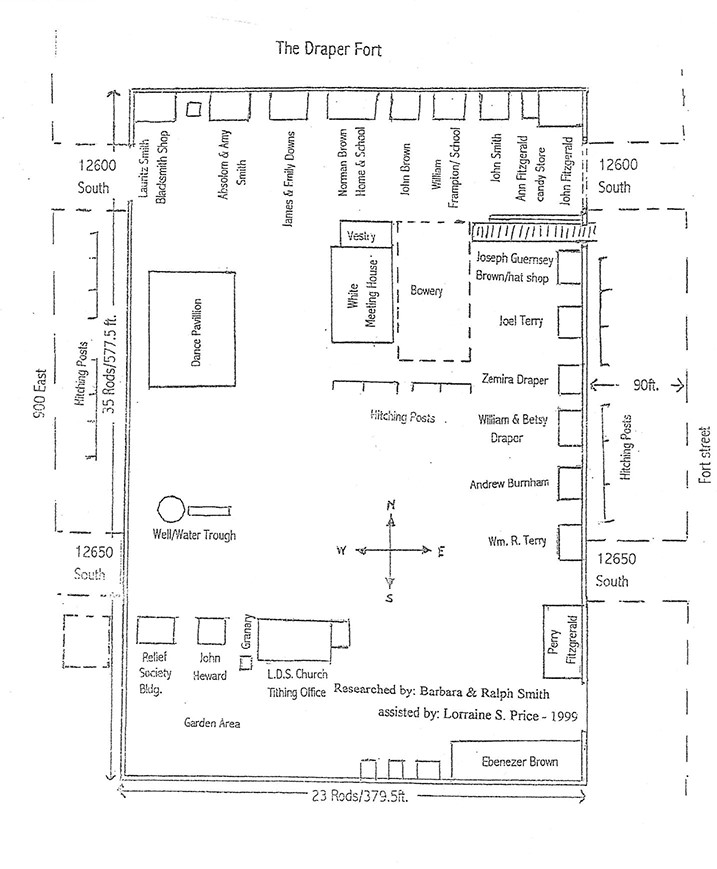

Originally, as noted by the marker, classes for the university were held in the home of John Pack, an early Mormon pioneer who is known to have helped settle the Salt Lake Valley. Pack himself notes in his journal entries, “I staid in the val[l]ey a fue [few] days and cut and hauled the first set of house logs that man ever hauled in this valley.”[2] The university was not immediately established upon the Mormons’ arrival, however, and LDS pioneers were often preoccupied with other responsibilities to the church and to the community. In 1848, not long after his arrival in the Great Basin region, Pack explains in his journal that he was redirected on a mission to France with elders John Taylor and Curtis E. Botton. Utilizing his knowledge from Europe, specifically his study of French educational institutions, Pack helped to structure the functioning of the University of the Deseret upon his return.[3]

Tuition was charged not in dollar amount; rather, Pack accepted natural resources like lumber as payment, and the resources were generally sold for profit. Classes in the Pack home were temporary, however, and, “…when the 13th ward schoolhouse was finished in the fall of 1851, the campus moved to this new building. About this time the university began to offer more resources and opportunities to students.”[4] Classes at the 13th ward schoolhouse unfortunately did not last long either due to financial constraints on the LDS population.

Due to economic insecurity of the Latter-day Saints in the formative years of their time in Utah, it was extremely difficult to continue classes at the University of the Deseret. In 1853, the university was forced to suspend operations due to insufficient funds. Despite this, classes were intermittently held at the Salt Lake City Council House, a building in downtown Salt Lake City used for government, civic, and community functions, until 1869 when John R. Park was hired as Principal and helped to establish a solid foundation for the university in Salt Lake.[5]

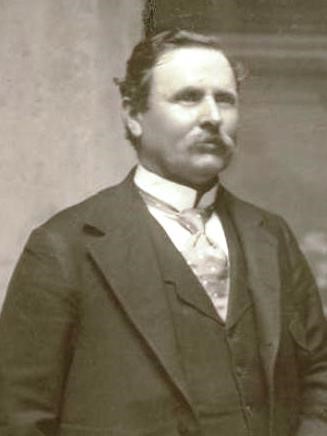

Park had been a practicing teacher in Draper since 1861 before he eventually became president of the University of the Deseret. Similar to Pack, John R. Park had toured Europe and used the enlightened modes of reason that he witnessed there to his advantage in order to effectively structure the education system in Utah.[6]

Still, Park was a baptized and practicing Latter-day Saint, and “like their lax attitudes toward separation of church and state, the Mormons did not make great efforts to distinguish between truth received from spiritual revelation or from empirical confirmation.”[7] The University of the Deseret and its curriculum was often centered around LDS doctrine, values, and industry. One example of unique study was the creation of a “Deseret Alphabet,” wherein “the Mormon-founded University of Deseret developed and promoted an alternative phonetic alphabet, modeled partly on Pitman shorthand.”[8] This contributed to the difficulty of attracting federal funding for the educational institution, due to overall negative attitudes towards Mormonism and efforts to contain the spread of LDS teachings. In the 1890’s, the University of Deseret began to adopt more secular teachings and policies, which highlights the contradiction between dominating religious authorities and the need for federal funding, which ultimately pushed the university to abandon hardline religious rhetoric. One such measure taken by the university was “In 1892, four years before statehood, an

amendment to the University of Deseret charter changed the name to the University of Utah.”[9] “Deseret” was a term taken from the book of Mormon and said to mean “honeybee.”[10] It was ultimately tossed out in favor of the US territorial name. This name change implied loyalty to the nation as opposed to Mormon religious authority, which helped establish good relations between the university and the US federal government.

Two years after the university’s name was formally changed to the “University of Utah,” congress ceded land from Fort Douglass which was established during the Civil War to the University for study and research purposes. “In 1894, Congress passed an act granting the university sixty acres of the land. Thirty-two more acres were granted in 1906 and another sixty-one in 1934.”[11] To this day, the University of Utah remains on the east bench of Salt Lake City.

For Further Reference:

[1] “University of Utah Sesquicentennial, 1850 – 2000.” Deseret University, 1850-1892 Marriott Library, https://www.lib.utah.edu/collections/photo-exhibits/deseret-university.php

[2] Pack, John. “Transcript.” Transcript | Church History Biographical Database, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/chd/transcript?lang=eng&name=transcript-for-john-pack-papers-1833-1882-item-15. (Primary Source)

[3] “France: Church Chronology.” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/history/global-histories/france/fr-chronology?lang=eng

[4] “The Beginning of the University of Utah: Historic and Prehistoric Publications.” J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, Utah State Historical Society, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6q52p0s/419269.

[5] University of Utah Sesquicentennial, 1850 – 2000.” https://www.lib.utah.edu/collections/photo-exhibits/deseret-university.php

[6] Peoplepill.com. “About John R. Park: American Academic (1833 – 1900): Biography, Facts, Career, Life.” Peoplepill.com, https://peoplepill.com/people/john-r-park

[7] “Fort Douglas-University of Utah Relations.” History to Go, 2 June 2016, https://historytogo.utah.gov/fort-douglas-university-utah-relations/.

[8] “Deseret Alphabet, p. 1” Utah State Historical Society. Salt Lake City, 2008. Mountain West Digital Library, https://utah-primoprod.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=digcoll_uuu_11dha_cp%2F436715&context=L&vid=MWDL. (Primary Source)

[9] “University of Deseret.” University of Deseret – The Encyclopedia of Mormonism, https://eom.byu.edu/index.php/University_of_Deseret.

[10] “Where Does the Word ‘Deseret’ Come from?” Book of Mormon Central, 20 Aug. 2020, https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/knowhy/where-does-the-word-deseret-come-from

[11] “Fort Douglas-University of Utah Relations.” https://historytogo.utah.gov/fort-douglas-university-utah-relations/.

[12] “Salt Lake City, Council House P.8: Classified Photographs.” J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, Utah State Historical Society , 15 Apr. 2014, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6c26cdt. (Primary Source)

[13] “University of Deseret p. 2” J. Willard Marriot Digital Library, Utah State Historical Society, 10 Apr. 2009, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6g73tvj. (Primary Source)