Write-up by Christopher Rich

Placed by: The monument does not describe what organization placed it. However, according to employees at the Peteetneet History Museum, it was funded by The People Preserving Peteetneet and installed by the Highway Department.

GPS Coordinates: 40.033313, -111.734020

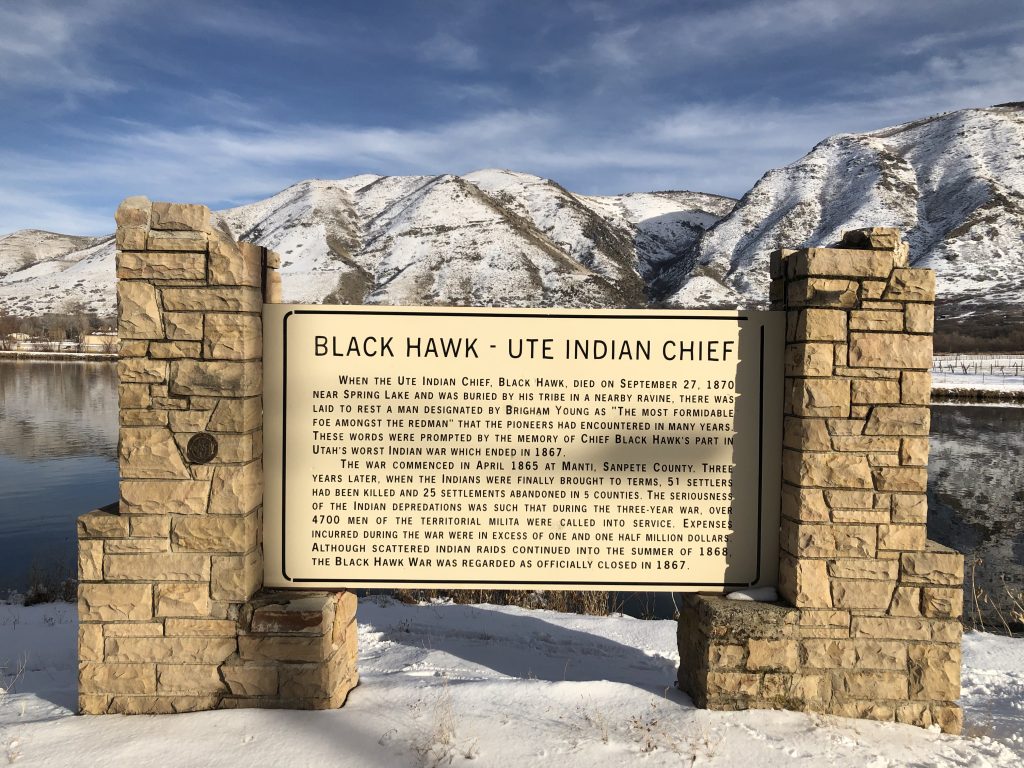

Historical Marker Text:

You are a fool for fighting your best friends, for we are the best and the only friends that you have in the world” wrote Brigham Young to the Ute Indian Chief Walkara in 1853, after the latter had engaged the settlers of Utah in their first major Indian war.

Angered because the whites had put an end to the Indian slave trade in the territory and had encroached upon their lands, the redmen found a pretext for beginning hostilities at Springville, July 17, 1853, when an Indian, while beating his squaw, was killed by a white man. The following day, Alexander Keele, a guard at Payson, was shot by Indians and the war was on. The policy of the white defenders was one of vigilant watch and limited offensive warfare. However before Governor Brigham Young led a peace mission into Walkara’s camp in May 1854 that ended the conflict, 20 whites had been killed including the U.S. Government surveyor Captain John W. Gunnison, who was massacred with 7 of his men near the present site of Hinckley, Utah.

Extended Research:

When the first Euro-American explorers came to Utah in 1776, the Western Ute were a non-equestrian people whose way of life was not very different from other local Indigenous people such as the Paiute and the Goshute. However, over the next thirty years, the Western Ute obtained horses and firearms and were integrated into New Mexican trade networks. The Ute developed a raid and trade economy in which they enslaved non-equestrian Indians in the Great Basin and traded them into New Mexico. In the mid-1820s, they also began to trade with American and British trappers. The Ute band leader Wákara (or Walker) eventually joined mountaineers such as Thomas “Peg-Leg” Smith in large-scale horse raids in California. By the time that Brigham Young led the Latter-day Saints to the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, Wákara had grown rich in a trade system based on stolen livestock, firearms, and slaves.[1]

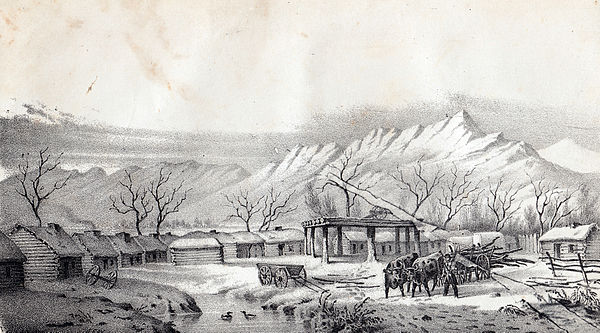

Brigham Young hoped that his people could avoid conflict with the Ute. He purposely chose to settle in the Salt Lake Valley rather than on the principal Ute lands in Utah Valley so as not to “crowd upon the Utes until we have a chance to get acquainted with them.”[2] Nevertheless, a small band of Timpanogos Ute soon began stealing Mormon livestock. In February 1849, a Latter-day Saint posse surrounded the band, and after the warriors refused to surrender, engaged in a two-hour battle in which 4-6 Timpanogos were killed. Soon afterwards a group of Mormon colonists entered Utah Valley to create a permanent settlement. Over the next year, incidence of theft and violence increased around the new Mormon colony at Fort Utah. In one instance, a group of Mormons killed a Ute named “Old Bishop” and attempted to cover-up the crime. After much cajoling by settlers and visiting military officers, Brigham Young finally authorized the territorial militia to carry-out a full-scale assault against the Timpanogos in March 1850. Young was not informed of the murder of Old Bishop, and later indicated that he would not have sent the militia had he known the truth.[3] But for the next year, the Latter-day Saints implemented an aggressive policy against “hostile” bands of Ute and Goshute. By June of 1851, Young abandoned this war policy on both fiscal and humanitarian grounds.

Despite the conflict in Utah Valley, the Mormons entered into an alliance with Wákara’s band of Ute in the summer of 1849. This alliance ultimately lasted for four years. Wákara believed that the Latter-day Saints would provide a local market for the spoils of his raiding activities, and that he could also continue to trade with the New Mexicans. However, the Mormons objected to the trade in Native American women and children that was an important component of Wákara’s business model. In some cases, Mormons refused to purchase children from Ute slavers who would then kill the children. This left the Mormons in a difficult position. They wanted to halt the slave trade, but worried that enslaved Indians were in immediate danger if the Mormons did not purchase them. In the winter of 1851-52, the Latter-day Saints prosecuted a group of New Mexican traders for engaging in the slave trade with the Ute. At the same time, the Utah Legislature passed a law permitting Mormons to purchase Indian slaves and hold them as apprentices for up to 20 years.

By the spring of 1853, Mormon restrictions on the slave trade were causing significant friction with Wákara’s band. This state of affairs was only exacerbated by the continued expansion of Mormon settlements onto Ute land. Threats were exchanged on both sides, but direct hostilities did not break out until the summer. On July 17, a Mormon settler in Utah Valley named James Ivie intervened in a physical altercation between a Timpanogos man and woman, mortally wounding the man. Brigham Young immediately wrote to Wákara and his brother Arapene and urged them to remain at peace.[4] Local Mormons also attempted to negotiate. But the relationship between the Saints and the Ute was too badly damaged. The next day, the Ute retaliated by killing a Mormon named Alexander Keel. Over the next several days, the Ute wounded several more Latter-day Saints in different locations. Militia leaders in Utah Valley quickly organized a punitive expedition and killed several Utes before Brigham Young ordered them to return home. But these events initiated a cycle of revenge that lasted for six months.

During the ensuing conflict, Brigham Young followed a strategy that has been described as “defense and conciliation.”[5] He ordered the militia to refrain from pursuing Ute raiders. Instead, he instructed Mormon communities to build forts and to send excess livestock to the Salt Lake Valley while he attempted to make peace. However, the Saints often ignored these directives and engaged in retributory attacks. On at least two occasions, the Mormons summarily executed unarmed Ute prisoners.[6] At the same time, the Ute relied on guerilla tactics, attacking small parties of Mormons or stealing livestock and then fleeing back into the mountains. The Ute sometimes mutilated the dead, further inflaming passions. One victim, Thomas Clark, was found scalped with his head smashed in and his heart removed.[7] By January 1854, 12 Mormons had been killed as had 24-34 Ute.[8] However, the infamous murder of Captain Gunnison and his mapping party by Pahvant Utes in October 1853 was unrelated to the larger conflict.[9]

Although the struggle between the Mormons and the Ute has come to be known as the Walker War, Wákara’s actual participation in hostilities is disputed. As early as July 22, the Mormons heard rumors that Wákara had counseled his band to seek peace and left the theatre of conflict.[10] By November, the Saints were convinced that Wákara’s band had split and that Wákara had gone south to winter with the Navajo. Other members of his band continued to fight until January 1854. Even so, Brigham Young entered into peace negotiations with Wákara during the spring. Wákara demanded the right to trade with the New Mexicans as before and to receive annual tribute for the occupation of Ute lands. In May 1854, Young and Wákara met in person. Young refused to accede to Wákara’s demands although Young did purchase at least one Paiute captive from the Ute leader. Nevertheless, the two men entered into a peace agreement. Wákara died early the following year. Although there was brief fighting with the Ute band leader Tintic in 1856, the Latter-day Saints and the Ute largely remained at peace for the next decade. In 1865, Western Ute leaders signed a treaty with the federal government in which they agreed to remove to a reservation in the Uinta Basin.

For Further Reference:

Primary Sources

Journal History of the Church, 1830-1972. Church History Library. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Young, Brigham. “Brigham Young to Wakara and Arapene,” July [18?], 1853. http://brighamyoungcenter.org/s/byp/item/1057?property%5B0%5D%5Bjoiner%5D=and&property%5B0%5D%5Bproperty%5D=7&property%5B0%5D%5Btype%5D=in&property%5B0%5D%5Btext%5D=1853&link=/s/byp/page/documents#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-3840%2C-254%2C11398%2C5075.

Secondary Sources

Alley, Jr., John R. “Prelude to Dispossession: The Fur Trade’s Significance for Norther Utes and Southern Paiutes.” Utah Historical Quarterly 50, no. 2 (Spring 1982): 104-123.

Christy, Howard A. “The Walker War: Defense and Conciliation as Strategy.” Utah Historical Quarterly 47, no. 4 (Fall 1979): 395-420.

Jones, Sondra G. Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019.

Wimmer, Ryan Elwood. “The Walker War Reconsidered.” MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 2010.

[1] Sandra G. Jones, Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019), 8-68; John R. Alley, Jr., “Prelude to Dispossession: The Fur Trade’s Significance for Norther Utes and Southern Paiutes.” Utah Historical Quarterly 50, no. 2 (Spring 1982): 104-123.

[2] Journal History of the Church, 1830-1972, 21 July 1847, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City, Utah).

[3] Jones, Being and Becoming Ute, 84-87.

[4] Brigham Young, “Brigham Young to Wakara and Arapene,” July [18?], 1853. http://brighamyoungcenter.org/s/byp/item/1057?property%5B0%5D%5Bjoiner%5D=and&property%5B0%5D%5Bproperty%5D=7&property%5B0%5D%5Btype%5D=in&property%5B0%5D%5Btext%5D=1853&link=/s/byp/page/documents#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-3840%2C-254%2C11398%2C5075.

[5] Howard A. Christy, “The Walker War: Defense and Conciliation as Strategy.” Utah Historical Quarterly 47, no. 4 (Fall 1979): 395-420.

[6] Wimmer, Ryan Elwood. “The Walker War Reconsidered.” MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 2010, 139-40, 144-45.

[7] Ibid, 143-44.

[8] Ibid, 155.

[9] Ibid, 148-49

[10] Ibid, 132-33.