Write up by: Jennifer Talkington

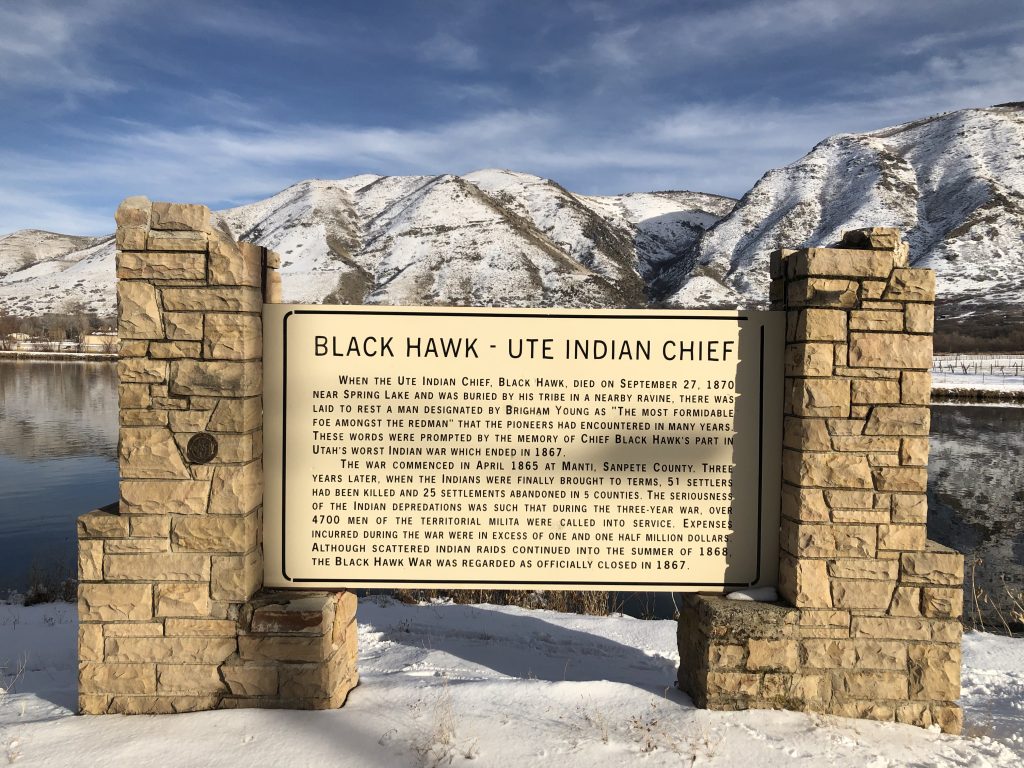

Placed By: Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT)

GPS Coordinates: 40 0’16” N 111 44’48” W

Historical Marker Text Transcript: “BLACK HAWK – UTE INDIAN CHIEF When the Ute Indian Chief, Black Hawk, died on September 27, 1870 near Spring Lake and was buried by his tribe in a nearby ravine, there was laid to rest a man designated by Brigham Young as “The most formidable foe amongst the Redman” that the pioneers had encountered in many years. These words were prompted by the memory of Chief Black Hawk’s part in Utah’s worst Indian war which ended in 1867. The war commenced in April 1865 at Manti, Sanpete County. Three years later, when the Indians were finally brought to terms, 51 settlers had been killed and 25 settlements abandoned in 5 counties. The seriousness of the Indian depredations was such that during the three-year war, over 4,700 men of the Territorial Militia were called into service. Expenses incurred during the war were in excess of one and one half million dollars. Although scattered Indian raids continued into the summer of 1868, the Black Hawk War was regarded as officially closed in 1867.”

Extended Research:

The Black Hawk War was fought between the Ute Indians and the Mormon settlers in central and southern Utah between 1865 and 1872. Tensions between the groups had been building since the Mormon settlers arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 due to struggles over resources. The Mormon settlers chose the best land to settle, took productive fisheries such as Utah Lake, took timber, drove game away and diverted critical water sources for irrigating crops, leaving the Native people of Utah destitute and starving.[1] After almost twenty years of living together in relative peace, tensions became too much. No one single event sparked the war, as many skirmishes were happening on a small scale all around central and southern Utah. However, many historians suggest that a disagreement between two men boiled over into warfare in April of 1865.[2] A young Ute man named Jake Arapeen rode into Manti with Black Hawk and met up with John Lowry, a Mormon settler and employee of the United States Indian Office, to discuss the tensions. The discussion led to a heated argument between the two men. In anger, John Lowry pulled Jake Arapeen off his horse by his hair and they fought on the ground. Seeing this as the lowest of insults, Jake Arapeen and Black Hawk rode off together and that day decided an all-out war against the Mormons was the only option.[3]

The fiercest of the fighting took place between 1865 and 1867. Both sides were perpetrators during this war and sadly most of the victims were innocent of depredations. The Circleville Massacre of April 1866 was one such horrible event to come out of the Black Hawk War. A friendly group of Paiute Indians were camped near Circleville when a church order came down to disarm the Indians. The Mormon settlers were interested in self-preservation and so decided to round up the Paiutes and put them in a meeting house under security. Two Paiutes managed to break free and were shot as they were getting away. Paranoia got the best of the settlers and they decided they should kill the twenty-four remaining Paiutes.[4] Brigham Young was disgusted by the murders and “later said that the curse of God rested upon the Circle Valley and its inhabitants because of it.”[5]

Also in 1866, the Ute’s raided horses and cattle from Scipio and the surrounding area totaling 350 head of cattle, a huge loss for Mormon settlers. As the settlers tried to regain their cattle, the Battle of Gravelly Ford began. The Mormons and the Utes exchanged gunfire, killing a 14-year-old Mormon boy and James Russell Ivie. During the battle, Black Hawk was shot in the stomach, but the Ute’s managed to escape.

In 1867, Black Hawk was sick from an infection caused by the bullet wound he received in the Battle of Gravelly Ford. He saw that his people could not win the war as the Mormon population kept increasing. Black Hawk decided he would go on a campaign of peace. He personally visited many Mormon villages he had raided to apologize for the pain he and his warriors caused. He was laid to rest on September 27, 1870 in the same place as his birth: Spring Lake Utah.[6]

The death of Black Hawk did not bring an end to this war. The Ute people were starving, their population decimated through disease and loss of game. Periodic raids to avoid starvation continued by the Utes until 1872.[7] It was in 1872 that the federal troops took control of the area as the Nauvoo Legion was dismantled. The federal troops strictly forced the Utes to remain on the Uintah Reservation. Once the Mormon settlers were free from raids, they were able to go back to previously abandoned settlements. They also used Chief Black Hawk’s raiding trails to expand their territory even further.[8] This historical marker is in need of an update, as we now know that the number of settlers killed was at least 70.[9] It is thought that at least 140 Native Americans died during this conflict, likely more. The result of the war for the Utes was a move to the Uintah Reservation, giving up their traditional lifestyle for a life of dependency on the United States Government. The result of the war for the Mormon settlers was the unimpeded colonization of Utah Territory, leading the way to statehood in 1896.[10]

[1] Gottfredson, Peter, ed. (1919). History of Indian Depredations in Utah. (Salt Lake City: Fenestra Books,2002), 20-22.

[2] Peterson, John Alton. Utah’s Black Hawk War. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1998), 16.

[3] Peterson, Black Hawk, 17.

[4] Jones, Sondra. Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019), 166.

[5] Wells, Quentin Thomas Wells. Defender: The Life of Daniel H. Wells. (Boulder: Utah State University Press, 2016), 280.

[6] Gottfredson, Depredations, 227.

[7] Jones, Becoming Ute, 172.

[8] Petersen, Black Hawk, 396.

[9] Peterson, Black Hawk, 2.

[10] May, Dean. Utah: A People’s History. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987).

For Further Reference:

Primary Sources:

Gottfredson, Peter, ed. (1919). History of Indian Depredations in Utah. Salt Lake City, Utah: Fenestra Books.

Secondary Sources:

May, Dean. Utah: A People’s History. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987).

Jones, Sondra. Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, 2019.

Peterson, John Alton. Utah’s Black Hawk War. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, 1998.

Wells, Quentin Thomas Wells. Defender: The Life of Daniel H. Wells. Boulder, Colorado: Utah State University Press, 2016.