Write-up by Julia Huddleston

Placed By: Division of State History. The building is on the national register of historic places

GPS: 40.789, -111.900

Historical Marker Text:

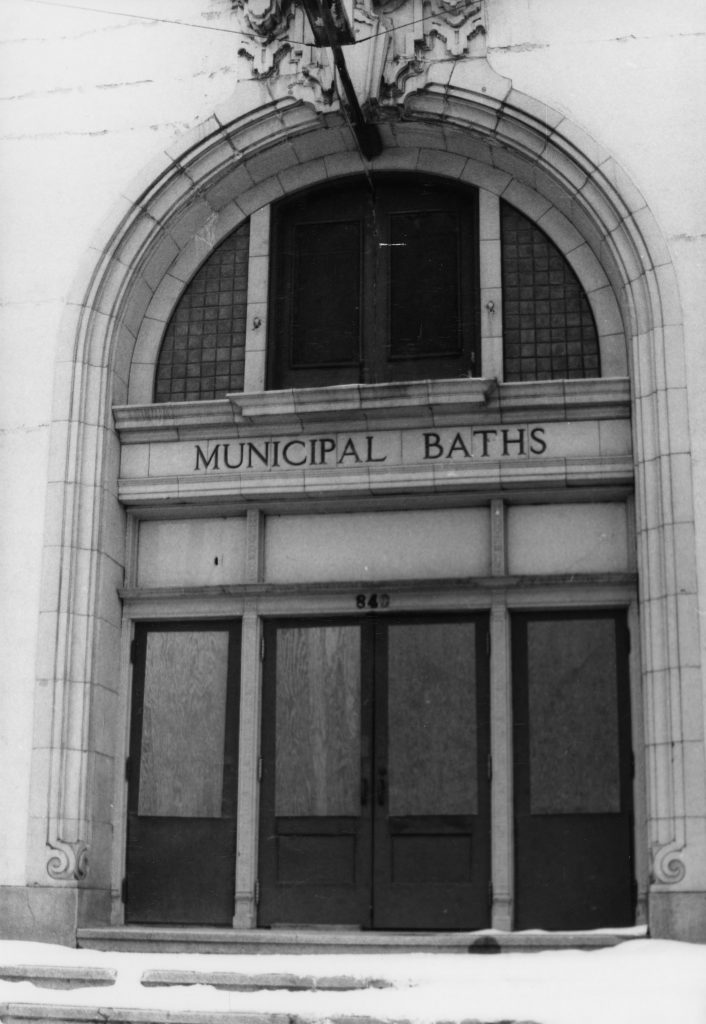

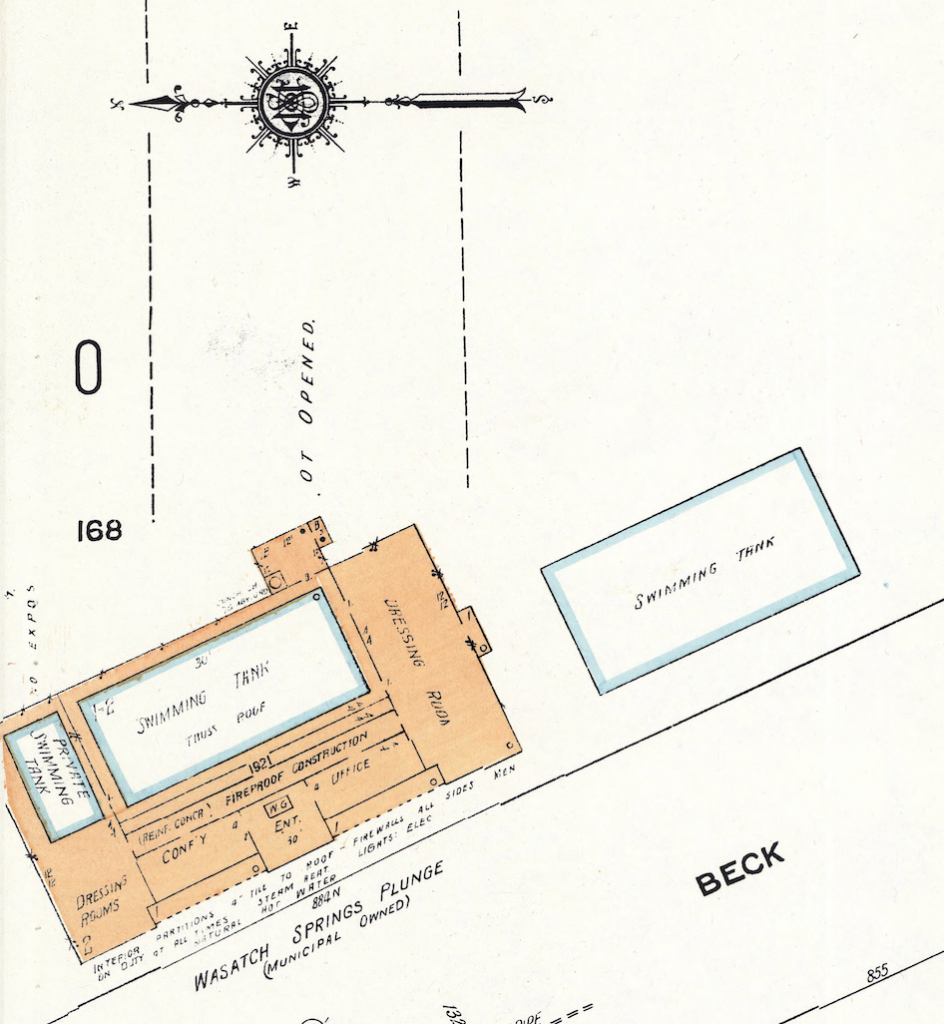

Built near several warm springs, the Wasatch Springs Plunge is significant for its Mission style architecture and as an early municipal recreational facility. The warm springs along this portion of the Wasatch Fault were used by Native Americans even before the arrival of the Mormon pioneers who quickly developed the springs and constructed numerous bathing facilities, praising the warm sulphurous [sic] water for its curative and rejuvenating qualities. This substantial masonry building was built by Salt Lake City in 1921 and replaced earlier frame buildings.

Designed by the noted local architecture firm of Cannon and Fetzer, the building exemplifies the Mission Style. The stuccoed walls, red tile roofs, curvilinear parapets, arched openings and arcades are characteristic of the Mission style which emanated from California at the end of the nineteenth century and was based on the old Catholic missions.

Due to problems with the water, deterioration of the structure, construction of newer pools and changes in demographics, the facility fell into disuse in the 1970s and was closed. It was later rehabilitated and reopened in 1983 as The Children’s Museum of Utah.

Marker placed in 1993.

Extended Research:

Built in 1921, the Wasatch Springs Plunge served as a municipal pool for fifty years, tapping into the natural hot springs at the far northern end of Salt Lake City. The building, located at 840 North and 300 West was built by noted architectural firm Cannon and Fetzer and is a striking example of Spanish Colonial Revival style architecture. In its heyday, the building had two pools, administrative offices, several private soaking tanks, a barbershop, a hairdresser, and men and women’s masseurs. Additionally, there were also five rooms available for overnight guests.[1]

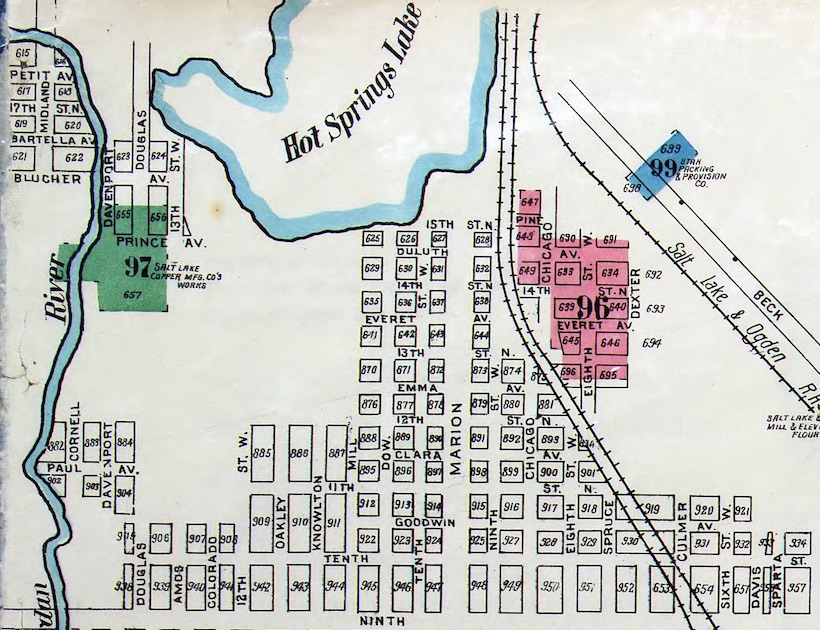

The Warm Springs have been utilized by all groups of people who call this region home. Historian Kathryn MacKay notes, “The 2-3 mile strip of hot springs and lake had been used for preceding centuries by the American Indians – Shoshones, Utes, Paiutes – who traveled through the area on hunting, foraging, trading, and social expeditions.”[2] It is likely that white fur trappers who were known to have visited the adjacent area also visited the springs. The first written encounter with the springs comes from a California-bound group, who followed Hastings Cutoff in 1846, and wrote of the warm water and its distinctly unpleasant odor. Erastus Snow, who, along with seven others, arrived in advance of Brigham Young’s wagon train, wrote about the Warm Springs on July 22, 1847. After describing the location, and the rocks nearby, he noted the temperature by writing, “We had no instrument to determine the degree of Temperature but suffice it to say that it was about right for scalding hogs.” Snow decided “The springs are the greatest facilities for a steam doctor I ever saw.” [3]

The permanent Euro-American settlement of the Salt Lake valley also marks the beginning of human-made structures intended to enhance the enjoyment of the natural springs. The springs were considered to have healing properties and were marketed not only for recreation but also for medicinal uses. In 1850, the Bath House opened and was within the purview of the neighboring Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) 19th ward bishop’s responsibilities. By 1864, this building had fallen into disrepair and was no longer operated by the LDS Church. Over the next several decades the facilities were used for recreational purposes and, in 1916, Salt Lake City assumed ownership. It was at this point when the current structure was built and would remain in near-constant use for the next 85 years.

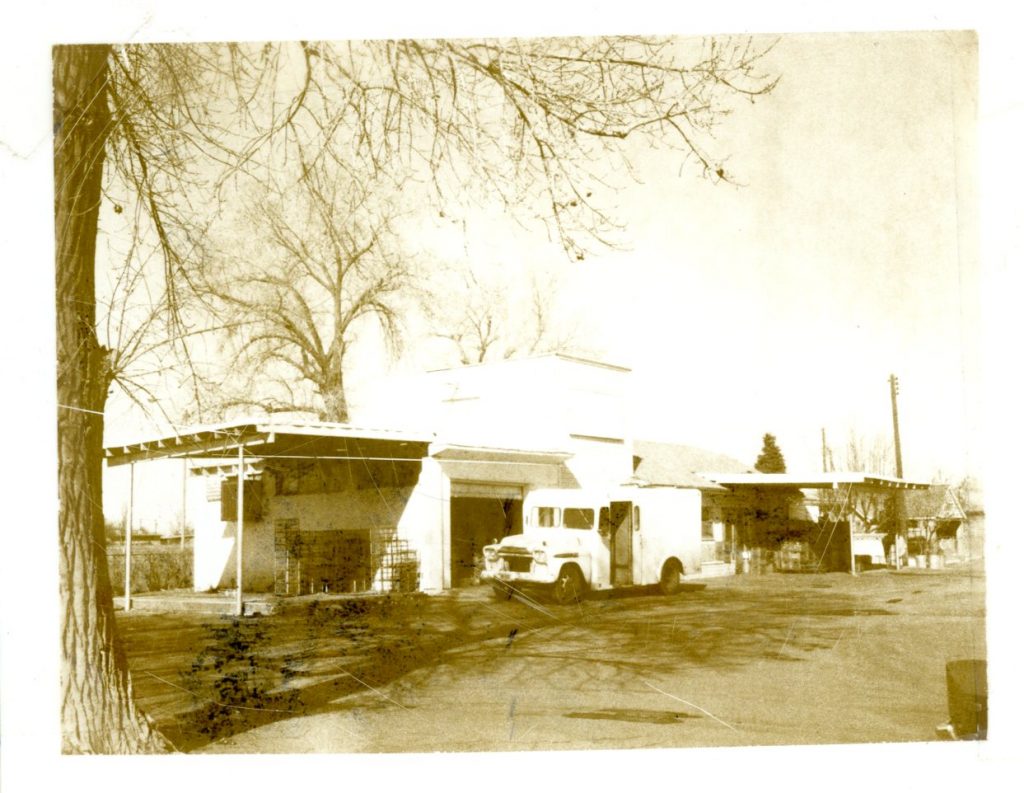

This period of the building’s history was not without problems. In 1946, concerns were raised over the sanitation of the water, and the city initially suggested chlorinating the pools. However, chlorine mixed with sulfur produces noxious chemicals, harmful to swimmers. As a compromise, the city decided to cap the natural hot springs, and the space was converted to a fresh-water, chlorinated pool.[4] Around that time, the pools began losing their appeal, and by the mid-1970s, they were no longer financially sustainable and were shuttered for nearly a decade before the Children’s Museum of Utah moved into the space in 1981.

Today, the future of the building is unknown. Placed on the historic registry in 1980, the building has not been occupied full-time since the Children’s Museum of Utah moved out in 2006. The Golden Spike Train Club of Utah uses the space to house and work on their model railroad projects, but their future there is not guaranteed.[5] In 2016, Salt Lake City began accepting proposals for development, but eventually ruled out the possibility of putting housing on the site. A local organization, the Warm Springs Alliance, is advocating for the building to be used as warm springs once again.[6] However, this proposal faces significant financial hurdles. As of spring 2019, the building’s future is unknown, but there is no shortage of interest and enthusiasm for utilizing this historic gem in downtown Salt Lake.

For Further Reference:

Primary Sources:

Erastus Snow Journal, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

Secondary Sources:

Lutz, Susan Juch. “Cleaned Up and Cleaned Out: Ruined Hot Springs Resorts of Utah.” GHC Bulletin (Energy and Geoscience Institute, University of Utah), 2004.

Jones, Darrell E. and W. Randall Dixon. “’It Was Very Warm and Smelt Very Bad’: Warm Springs and the First Bathhouse in Salt Lake.” Utah Historical Quarterly, Volume 76, Number 4 (2008): 212-226.

MacKay, Kathryn. “National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Wasatch Springs Plunge.” United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, 1980.

McFarland, Sheena. “Whatever happened to … Wasatch Springs Plunge?” The Salt Lake Tribune, December 23, 2014.

McLane, Michael. “The Children’s Museum.” Mapping SLC, http://www.mappingslc.org/this-was-here/item/243-the-children-s-museum.

McLane, Michael. “Past and Present Collide at Warm Springs.” Catalyst Magazine, December 1, 2017.

[1] Kathryn MacKay. “National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Wasatch Springs Plunge.” United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service, 1980, 9.

[2] MacKay, “National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form,” 6.

[3] Erastus Snow Journal, July 22, 1847, as quoted in Darrell E. Jones and W. Randall Dixon. “‘It Was Very Warm and Smelt Very Bad’: Warm Springs and the First Bathhouse in Salt Lake.” Utah Historical Quarterly, Volume 76, Number 4 (2008): 212-226.

[4] MacKay, 9.

[5] Michael McLane. “The Children’s Museum.” Mapping SLC. http://www.mappingslc.org/this-was-here/item/243-the-children-s-museum. Accessed March 15, 2019. See also http://www.goldenspiketrainclubutah.org/ for information on the model train organization.