Write-up by Kaleigh McLaughlin Undergraduate B.A. History and International Studies, University of Utah, University of South Dakota

Coordinates: 40.7601° N, 111.8243° W

Transcript:

Erected by the German-Americans of the United States of America. And the American Legion of the State of Utah. Unveiled on the 30th of May 1933.

Arno A. Steinicke. Sculptor

Transcript:

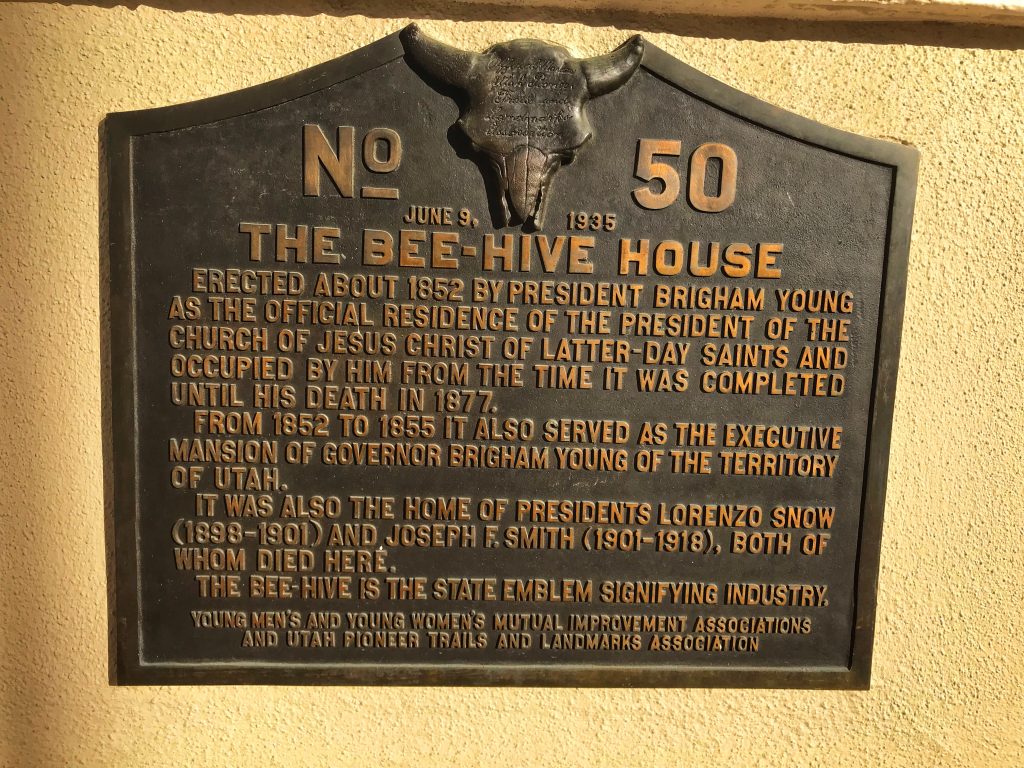

German War Memorial

The German War Memorial to the Victims of War was erected by the German-Americans of the United States of America in cooperation with the American Legion of the State of Utah in memory of the men who died while interred at Fort Douglas during World War I.

The monument was designed and constructed by Arno Steinicke. It was dedicated on Memorial Day, May 30, 1933.

Fifty-five years later, in 1988, the monument was restored by sculptor Hans Huettlinger and his son John under arrangements made by the German Air Force and German War Graves Commission.

Today the restored monument stands in of the victims of both World Wars who are buried here in Fort Douglas Cemetery and to the victims of war and despotism throughout the world.

Transcript Right Column in German:

Das Deutsche Ehrenmal der Kriegstoten wurde von den Deutsch-Amerikanern in Zusammenarbeit mit der American Legion of the State of Utah zum Gedenken an die als Internierte und Kriegsgefangene des I. Weltkrieges in Fort Douglas verstorbenen Deutsch errichtet.

Kunstlerischer Entwurt und Ausfuhrung der Arbeiten erfolgeten durch Arno A. Steinecke. Das Ehrenmal wurde am Memorial Day, den 30. Mai 1933 eigeweiht.

Nach 55 Jahren wurde das Ehrenmal 1988 auf Initiative der Deutsch Luftwaffe im Zusammenwirken mit dem Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgraberfursorge e.V. durch den Bildhauer Has Huttlinger und seinen Sohn John aus Salt Lake City restauriert.

Das Ehrenmal dient nun dem Gedenken der Opfer der beiden Weltkriege, die hier in Fort Douglas ruhen sowie darbuer hinaus allen Opfern von Kriegen und Gewaltherrschaft in der Welt.

Transcript:

The Last Resting Place of 21 German Prisoners of War who died at Fort Douglas during the World War

1917-1918

1917-1918

Henry L. Zinnel

Frank Stadler

Arthur Ruebe

Karl G. W. Blaase

Erich Laevemann

Friedrich O. Hanf

Walter J. Piezareck

Emil Laschke

Roko Zilko

Felix Behr

Maximilian Kampmann

Max Leopold

Joseph Fuckola

Herman Lieder

Stanislaus Lewitski

Georg Schmidt

Charles Morth

Frank Benes

Adolf Wachenhusen

Herman German

Walter Topff

Extended Research

On April 6, 1917 the United States unilaterally declared war on Germany. This moment marked the beginning of U.S. entry into the First World War. Accompanying U.S. entry into the war were all of the complications including the logistical, and tactical issues associated with war. One such issue the U.S. had to face was the treatment of ‘enemy aliens’. “Enemy aliens were defined as males born in Germany over the age of fourteen who have not been naturalized[1]”. As U.S. involvement in WWI progressed the ‘enemy alien’ classification was broadened to include Austro-Hungarians as well.

German Consul and Memorial Designer Steinicke Visiting the Memorial. Salt Lake Telegram, May 29, 1937

A person classified as ‘enemy alien’ was restricted in their freedom of speech and their mobility. Specifically, “enemy aliens were not allowed to write, print, or publish any attack against the United States or against anyone in the civil service, armed forces or the local municipal government[2]” Furthermore, “no alien enemy could depart the United States without a permit except under court order[3]”. Under section 4067 of the Revised Statutes of the United States, enemy aliens who violated, or were suspected of violating these prohibitions were subject to arrest, internment, and removal.

Fort Douglas, Utah was to be the site of one of three designated camps during WWI. “On May 2, 1917 [a] public announcement was made that Fort Douglas was to be the site of one of three internment camps for German prisoners of war taken from naval vessels[4]”. However, as U.S. involvement in the Great War continued, hysteria and paranoia about German spy plots increased. This occurred alongside a rise in arrests of enemy aliens for suspected subversive activities by U.S. Marshals. As a result, the designation of Fort Douglas changed. Originally, the camp was to contain German naval prisoners of war, however, this designation changed to include both naval prisoners of war, and enemy aliens. In March of 1918, all of the remaining naval sailors were moved to Fort McPherson in Georgia and the camp at Fort Douglas evolved into an internment camp for enemy aliens[5]. This change has particular significance for the German War Memorial at the at the Fort Douglas cemetery. Out of the 21 names listed on the German War Memorial, only one is a naval prisoner of war (Stanilaus Lewitski), the rest are enemy aliens.

Salt Lake Telegram, May 30, 1935

Fort Douglas was “chosen for its central locality and its proximity to a main rail line[6]” The proximity to the railroad is the critical selection criteria, because the railroad would easily facilitate the transportation of interned aliens and prisoners of war. The ease of transportation was crucial to the selection of Fort Douglas because of the locations of the two other internment camps. “The other two camps were located at Fort McPherson and Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia[7]”. This meant that Fort Douglas was the only location west of the Mississippi where prisoners of war and interned aliens could be detained. “The civilian enemy aliens were rounded up by local authorities in most western states including Texas, California, Arizona, Washington, Oregon, Nebraska, and South Dakota[8]” and then interned at Fort Douglas.

Life at Fort Douglas was different depending on whether you were a prisoner of war or an enemy alien. From the outset German prisoners of war were physically separated from the interned enemy aliens. This was an intentional action as specified by a letter to the inspector general of the army stating that there must be an that there must be an “absolute separation of Prisoners of War from interned aliens by sending the former class to the War Prison Barracks, at Fort McPherson, Georgia”. The two groups at Fort Douglas enjoyed different privileges and experienced vastly different treatment throughout their stay at the camp. Inspections of the War Prison Barracks by the Swiss Legation demonstrate the differences between the two camps. In 1917, the barrack inspection of the prisoner of war camp “found it [the camp] in all respects excellent. The only problem was the athletic field. It was found to be too small[9]”. However, with regard to the inspection of the enemy alien camp the Swiss Legation concluded: “To attend church services, civilians [enemy aliens] had to make a request. Civilians were not allowed to partake in activities in the Y.M.C.A…persons suffering from Syphilis were not separated from other prisoners[10]”. Furthermore, there was a note about the increasing antagonism and animosity between the guards and the enemy aliens.

The experiences of Stanislaus Lewitski (a war prisoner) and Heinrich Ludwig (Henry L) Zinnel (enemy alien), underscore the differences between the two groups at Fort Douglas.

“An illiterate machinist employed at the Southwestern Machine Shop in El Paso, was working the day of his arrest. Heinrich Ludwig Zinnel, a thirty-five-year-old native of Germany, was making $4.50 per day when, on December 17, 1917, he was arrested and taken to the county jail at El Paso…Zinnel’s property was confiscated upon arrest and he remained at the country jail until eight days later when he was taken to Fort Douglas, on Christmas Day[11]”.

Cunningham continues Zinnel’s story noting that Zinnel accidentally injured himself while on the way to Fort Douglas. Visits to doctors proved to be ineffective, with one doctor accusing Zinnel of faking his illness. However, upon arrival at Fort Douglas Zinnel was desperately ill. He was suffering from fevers and losing weight. A roommate of Zinnel at Fort Douglas noted that Zinnel went from being about 180 pounds to 90. The doctor who attended Zinnel believed he was suffering from acute gastritis from some sort of poisoning. On June 1, 1918 Zinnel died. “A death certificate was not filed with the State of Utah, which was required by state law, and as a posthumous insult, his body was taken to be buried In the Fort Douglas Cemetery in a garbage wagon[12]”.

It is significant to contrast the treatment of Zinnel with that of another detainee at Fort Douglas. Stanislaus Lewitski, was one of the prisoners of war. Lewitski was a member of the SMS Cormoron, a ship which was captured and destroyed near Guam. Lewitski sustained a fatal injury while doing some gymnastics at the Y.M.C.A. Lewitski suffered from a broken spinal column and died within a few days of receiving his injuries. While both Zinnel and Lewitski may have died at Fort Douglas their treatment after death is where those similarities end. In contrast to Zinnel, Lewitski was taken and “buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery with full honors[13]”. The comparison in treatment after death between Zinnel and Lewitski underscores the differences between prisoners of war and enemy aliens at Fort Douglas. Another experience highlighting this difference was that of Emil Laschke. He “was an interned alien, but was a naval officer by trade. Hentschel [another inmate] recalled, ‘one of the dead, a Junior Officer in the Navy, Emil Laschke, was mocked by the placing of a gray cross upon his body and he was refused a grave stone[14]’”.

The differences in treatment between the war prisoners and enemy aliens, offer insights into the perceptions of Americans of the time about these groups. The Naval prisoners held at Fort Douglas were legitimate combatant actors in war. These were patriotic men fighting for their nation. In this regard, they were very similar to their American counterparts. However, enemy aliens were perceived differently. The classification of these people ‘enemy aliens’ has strong and significant connotations, which could have helped to shape perceptions of Americans about such people. The plethora of propaganda and paranoia towards enemy aliens clearly illustrates what the perceptions of Americans were towards this group. Enemy aliens were perceived as dishonorable combatants. They were spies and defectors of malicious intent who embedded themselves among the general populace seeking subterfuge. They were a strange people who had refused assimilation into American life, and who had more importantly, refused American citizenship. All of these factors combined helped to make enemy aliens especially suspect during the war years.

However, it is important to note that enemy aliens were civilian noncombatants living in the United States. Many were immigrants who became trapped behind enemy lines with the declaration of war. Often, enemy aliens, were people negatively affected by wartime policy through no fault of their own. Many of the enemy aliens, due to vague laws, rumors, and suspicion were persecuted, arrested, and interned with little to no recourse. The true tragedy of camps like Fort Douglas is evidenced by the lives of those who lived and died within such camps. Interment, meant the loss of jobs, social isolation and stigmatization, and could also mean death. In the case of Fort Douglas, each of the 21 men interned were people with the agency to succeed and flourish within the United States. It is a somber truth that the internment of these men resulted in their deaths denying them such opportunities. But, it is this somber truth which demonstrates the need for historical research to serve as documentation, but more importantly as a remembrance for those who lived and died at the Fort Douglas internment camp during World War I. What follows are short biographical sketches of the men whose names are listed on the historical marker at the Fort Douglas cemetery. The majority of the men died of illness related to the global Spanish Influenza outbreak that killed forty million people worldwide: during World War I.

Arthur Ruebe

According to his death certificate, Arthur Ruebe was interned alien enemy no. 1150. He was a merchant born in Erfurst, Thueringis, Germany. His mother and father are unknown, however, he was married and therefore survived by a wife.

Arthur Ruebe was interned alien enemy no. 1150. He was a merchant born in Erfurst, Thueringis, Germany. His mother and father are unknown, however, he was married and therefore survived by a wife.

Ruebe died on December 22, 1918, at the age of 44, the cause of death was identified as Bronchio-pneumonia following influenza. The afflicting illness lasted 19 days. Rube was attended to by the leading doctor of War Prison Barracks Three, William F. Beer. He was buried at the Fort Douglas Cemetery on December 23.

Charles Morth

According to his death certificate, Charles Morth was interned alien enemy no. 1054. He was born in Krukenberg, Germany. His mother and father are unknown. Morth was married and survived by a wife. Morth died on December 1, 1918 at age 50 from pneumonia, a condition which affected him for two days. Influenza is listed as a contributory affliction. Morth was also attended by Dr. Beer. He was buried at Fort Douglas Cemetery, December 2, 1918. The Salt Lake Tribune published notice of Morth’s death.

Emil Laschke

The death certificate of Emil Laschke lists him as German Prisoner of War no. 773.  Laschke was a machinist mate from Breslau, Silesia, Germany. His father was Heinrich Laschke, his mother is unknown. At his time of death he was unmarried. Laschke died on December 3, 1918 at the age of 25 from influenza. Bronchial pneumonia is listed as a contributory affliction. The cause of death and afflicting conditions lasted 9 days. Laschke was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on December 4, 1918. On December 5, 1918 the Salt Lake Telegram documented Laschke’s death.

Laschke was a machinist mate from Breslau, Silesia, Germany. His father was Heinrich Laschke, his mother is unknown. At his time of death he was unmarried. Laschke died on December 3, 1918 at the age of 25 from influenza. Bronchial pneumonia is listed as a contributory affliction. The cause of death and afflicting conditions lasted 9 days. Laschke was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on December 4, 1918. On December 5, 1918 the Salt Lake Telegram documented Laschke’s death.

Erich Laevemann

Erich Laevemann is listed as Prisoner of War no. 813. He was born in Duisburg on the Rhine, Germany. His mother and father are listed as unknown. At the time of his death he was unmarried. Laevemann died on December 10, 1918, at age 22 of bronchial pneumonia. A contributory affliction is listed as influenza. The primary and contributory illnesses lasted 6 days. Attended to by Dr. Beer, Laevemann was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on December 12, 1918. No newspaper sources have been discovered documenting the death of Laevemann.

Felix Behr

According to his death certificate, Felix Behr is listed as interned enemy alien no. 1151. Behr was born in Stotzheim, Alsace. His occupation is listed as a jeweler. His parents are unknown and at his time of death he was unmarried. Behr died on November 29, 1918 at the age of 32 from influenza complicated by pneumonia. His influenza lasted for seven days, and the pneumonia developed on the third day. At his time of death Behr had lived at Fort Douglas for three months and two days. He was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 30, 1918. The Deseret News and Ogden Standard reported Behr’s death shortly thereafter.

Frank Benes

Frank Benes is listed as interned alien enemy no. 914. He was born in Germany in 1894. His parents are unknown. He worked as a miner and at the time of his death he was unmarried. Benes died on November 6, 1918 at age 24 from pneumonia, lobar, bi-lateral. At his time of death, Benes had resided at Fort Douglas for one month and eight days. He was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 7, 1918. The Deseret News and Salt Lake Tribune reported Benes death shortly thereafter.

Herman Lieder

Herman Lieder is listed as interned alien enemy no. 889. He was born in Gera, Turingen, Germany to Paul and Lina Lieder on January 24, 1894. Lieder was a coppersmith and at the time of his death was unmarried. Lieder died on November 18, 1918 at age 24 from pneumonia, pyogenic, bi-lateral, lobar lasting three days. A contributory affliction is listed as a severe cold which lasted one day. At his time of death, Lieder had resided at Fort Douglas for seven months. He was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 19, 1918. On November 20, 1918 the Salt Lake Tribune reported Lieder’s death.

He was born in Gera, Turingen, Germany to Paul and Lina Lieder on January 24, 1894. Lieder was a coppersmith and at the time of his death was unmarried. Lieder died on November 18, 1918 at age 24 from pneumonia, pyogenic, bi-lateral, lobar lasting three days. A contributory affliction is listed as a severe cold which lasted one day. At his time of death, Lieder had resided at Fort Douglas for seven months. He was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 19, 1918. On November 20, 1918 the Salt Lake Tribune reported Lieder’s death.

Joseph (Joe) Fuckala

According to his death certificate, Joseph Fuckala is listed as interned alien enemy no. 738. He was born in Zelo-Orda, Croatia to Latzko Fukala and Anna Sullitsch. Fuckala was a carpenter and at the time of his death he was unmarried. Fuckala died on November 23, 1918, at age 30 of Spanish influenza complicated with pneumonia hemorrhages. The affliction lasted three days. At his time of death, Fuckala had resided at Fort Douglas for seven months and twenty-five days. He was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 24, 1918.

Max Leopold

According to his death certificate, Max Leopold is listed as interned alien enemy no. 584. Leopold was born in Germany, his parents are unknown. Leopold’s occupation is unknown. At his time of death he was unmarried. Leopold died on November 24, 1918 age 32 of pneumonia hemorrhages bi-lateral lasting one and-a-half days. A contributory affliction, Spanish influenza is listed as lasting three days. At the time of his death, Fuckala had resided at Fort Douglas for one year three months and twenty-four days. He was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 25, 1918. No newspaper sources were found to report on Leopold’s death.

Maximilian Kampmann

Maximilian Kampmann is listed as interned alien enemy no. 597.  Kampmann was born in Elberfeld, Germany, his parents are unknown. Kampmann was a well-respected doctor, specifically a psycho-pathologist who had lived and worked in the Utah area since 1916. Kampmann died on November 26, 1918 at age 29 of pneumonia lasting three days and influenza lasting six days. At the time of his death Kampmann resided at Fort Douglas for one year two months and twenty-six days. Kampmann had at some point formerly resided in Sper Lake, Los Angeles. Kampmann was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 28, 1918. The Ogden Standard, the Sun, the Salt Lake Tribune, and Salt Lake Telegram all reported on Kampmann between the period of 1916-1918.

Kampmann was born in Elberfeld, Germany, his parents are unknown. Kampmann was a well-respected doctor, specifically a psycho-pathologist who had lived and worked in the Utah area since 1916. Kampmann died on November 26, 1918 at age 29 of pneumonia lasting three days and influenza lasting six days. At the time of his death Kampmann resided at Fort Douglas for one year two months and twenty-six days. Kampmann had at some point formerly resided in Sper Lake, Los Angeles. Kampmann was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on November 28, 1918. The Ogden Standard, the Sun, the Salt Lake Tribune, and Salt Lake Telegram all reported on Kampmann between the period of 1916-1918.

Roko Zilko

The death certificate for Roko Zilko does not specify an interned alien enemy status. However, Zilko was born on the Island of Vys Dalmatia. Zilko’s occupation is listed as a laborer. His parents are unknown. At the time of his death he was unmarried. Zilko died of pneumonia at age 36 on November 30, 1918. The pneumonia developed on the fourth day while he was suffering from influenza for seven days. At his time of death Zilko had resided at Fort Douglas for one month and twenty-nine days. A former residence is listed as possibly Austria (the word Austria is accompanied by a question mark). Zilko was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on December 1, 1918. No newspaper sources were found to report on the death.

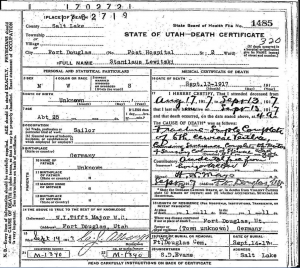

Stanilaus Lewitzki

In a similar situation as Zilko, the death certificate of Stanilaus Lewitzki does not list a prisoner of war number. However, Lewitzki was born in Germany. His parents are unknown and at the time of his death he was unmarried. Lewitzki was a sailor serving on the SMS Cormoron. Lewitzki died on September 13, 1917 at the age of 25 from a fractured spinal column with specific damage to the sixth cervical vertebrae. This injury was sustained while partaking in gymnastic activities at the prison camp. Lewitzki was admitted to the War Barracks Hospital on August 17, 1917. Lewitzki was attended by Dr. H. May and at the time of his death he had resided at Fort Douglas for one month and eleven days. Lewitzki was buried at Fort Douglas on September 14, 1917. The Salt Lake Telegram reported his death shortly thereafter.

Lewitzki died on September 13, 1917 at the age of 25 from a fractured spinal column with specific damage to the sixth cervical vertebrae. This injury was sustained while partaking in gymnastic activities at the prison camp. Lewitzki was admitted to the War Barracks Hospital on August 17, 1917. Lewitzki was attended by Dr. H. May and at the time of his death he had resided at Fort Douglas for one month and eleven days. Lewitzki was buried at Fort Douglas on September 14, 1917. The Salt Lake Telegram reported his death shortly thereafter.

Walter J Piezareck

Walter J Piezareck is listed as interned alien enemy no. 862. He was born in Postdam, Germany. His parents are unknown and at his time of death Piezareck was unmarried. His occupation is listed as a laborer. Piezareck died on December 6, 1918 at the age of 31 from bronchial pneumonia. Influenza contributed to his death; both afflictions lasted nine days. Piezareck was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried in the Fort Douglas Cemetery on December 6, 1918. No newspaper sources were discovered to report his death.

Walter Toppf

Walter Toppf is listed as interned alien enemy no. 867. Toppf was born in Germnay to Louise Toppf. The birthplace of Louise Toppf is listed as W. Plumental St. Berlin, Germany. At his time of death his father and marital status were unknown. Toppf was an artist, specifically he was a painter. Toppf died on May 16, 1919 at the age of 33, from hemorrhage and the contributory affliction is listed as pulmonary lobar complications, both of which lasted for one month and twenty-four days. At his time of death, Toppf had resided at Fort Douglas for ten months and eight days. Toppf was attended by Dr. Beer and was buried on May 16, 1919. On May 17, 1919 the Salt Lake Tribune reported Toppf’s death.

Zinnel, Stadler, Blaase, Hanf, Schmidt, Wachenhusen, and German

The aforementioned enemy aliens had no death certificates filed with the State of Utah. As such, there is extremely limited information on the lives of these men. Henirich Ludwig Zinnel, as previously mentioned was from El Paso. He died on June 1, 1918 from acute gastritis. He was known to be a laborer. Frank Stadler was an interned enemy alien who lived and died at Fort Douglas; any further information in unknown. Karl Johann W. Blaase was an interned enemy alien who lived and died at Fort Douglas. A ledger of interned enemy aliens revealed that Blaase was arrested on May 24, 1918, and he was sentenced to interment on July 5, 1918. According to historian Raymond Cunningham, Friedrich Otto Hanf:

“was one of those brought to Fort Douglas after the War, and was despondent over being there. As Christmas 1919 approached, Hanf was more depressed than usual. Fellow prisoners noticed that he was regretting the arrival of Christmas. At 7:30 a.m., Christmas morning, Hanf’s body was found hanging by a bedsheet from a rafter in his barracks[15]”.

The ledger of interned aliens at Fort Douglas also reveals that Hanf was arrested on December 7, 1919, and sentenced to internment on December 23, 1919.

Georg Schmidt and Adolf Wachenhusen were interned enemy aliens who lived and died at Fort Douglas with no further information known about their identities. Herman German was an interned enemy alien who lived and died at Fort Douglas. It is unlikely that Herman’s last name was German. It is more likely that his last name was unknown and he was known as ‘Herman the German,’ however, any further information is unknown.

Sources:

Primary

Beer, William F. Arthur Rube Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. December 23, 1918.

Beer, William F. Charles Morth Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. December 3, 1918.

Beer, Willian F. Emil Laschke Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. December 4, 1918.

Beer, William F. Erich Laevemann Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. December 11, 1918.

Beer, William F. Felix Behr Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. November 30, 1918.

Beer, William F. Frank Benes Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. November 7, 1918.

Beer, William F. Herman Lieder Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. November 18, 1918.

Beer, William F. Joseph Fuckala Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. November 24, 1918.

Beer, William F. Max Leopold Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. November 24, 1918.

Beer, William F. Maximilian Kampmann Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. November 28, 1918.

Beer, William F. Roko Zilko Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. November 30, 1918.

May, H. Stanilaus Lewitzki Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. September 13, 1917.

Beer, William F. Walter J Piezareck Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. December 6, 1918.

Beer, William F. Walter Toppf Death Certificate. Utah State Archives. May 16, 1919.

Salt Lake Tribune. Death of Charles Morth. January 13, 1918.

Deseret News. Prisoner at Fort Douglas Dead. November 20, 1918.

Deseret News. Frank Benes. November 8, 1918.

Ogden Standard. Influenza at Fort Douglas. November 30, 1918.

Odgen Standard. Kampmann to be interned for War. November 2, 1917

Salt Lake Telegram. Editorial by Max Kampmann. January 1, 1916

Salt Lake Telegram. Death of Emil Laschke. December 5, 1918

Salt Lake Telegram. Death of Stanilaus Lewitzki. N.d.

Salt Lake Tribune. Death of Walter Toppf. May 7, 1919.

Salt Lake Tribune. Social Notes from Utah Towns. September 9, 1916.

Salt Lake Tribune. Lieder Buried at Post. November 20, 1918.

Salt Lake Tribune. Frank Benes Influenza Death. N.d.

Salt Lake Tribune. Kampmann Appeal. September 28, 1917.

Salt Lake Tribune. Kampmann Arrest Causes Stir. September 20, 1917.

Salt Lake Tribune. Kampmann Taken by Federal Agents. September 19, 1917.

Salt Lake Tribune. Kampmann to be interned for War. November 2, 1917.

The Sun. Suspected German Spy now Making Appeal. Price, UT, October 5, 1917.

Secondary

Cunningham, Raymond Kelly Jr. Internment 1917-1920; A History of the Prison Camp at Fort Douglas, Utah, and the Treatment of Enemy Aliens in the Western United States. Department of History, University of Utah, Call Number D7.5 C85 1976.

Powell, Allan Kent. The German-speaking Immigrant Experience in Utah. Utah Historical Quarterly, Volume 52, Number 4, Fall 1984.

[1] Raymond Kelly Cunningham Jr., “Internment 1917-1920; A History of the Prison Camp at Fort Douglas, Utah, and the Treatment of Enemy Aliens in the Western United States,” (Master’s thesis. Department of History, University of Utah, 1976), 16.

[2] Ibid., 16

[3] Ibid., 16

[4] Allan Kent Powell, “The German-speaking Immigrant Experience in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 52(Fall 1984), 324.

[5] Cunningham, 96.

[6] Cunningham, 3

[7] Powell, 326

[8] Powell, 325

[9] Cunningham, 94

[10] Cunningham, 107

[11] Cunningham, 41

[12] Cunningham, 42

[13] Cunningham, 90

[14] Cunningham, 157

[15] Cunningham, 167