Pioneers of Antimony

Write-up: Eric Cecil Montague

Placed By: Daughters of Utah Pioneers Forrest Camp · · · Garfield County (1949)

G.P.S. Coordinates: 38° 6.907′ N, 111° 59.8′ W

Historical Marker Text:

In 1873, Albert Guiser and others located in a fertile meadow, which they named Grass Valley. Surveyors camped on a stream, lassoed a young coyote and called the place Coyote Creek. The first L.D.S. settlers were Isaac Riddle and family, who took up land on the east fork of the Sevier River. Later, a school house was built, and the Marion Ward organized with Culbert King as bishop. In 1920 the name was officially changed to Antimony after the antimony mines east of the valley.

A picture on the day of the dedication of the marker with Antimony townswomen – Amber Riddle and Maude Wiley on the left and Esther Mathews and Ethel Savage on the right. (Courtesy of the Mayor’s Office – Antimony, Utah)

Extended Research:

The history of Antimony is a story of diverse groups making a home in a beautiful valley. Much like the story of Utah at large, these groups consisted of Native Americans, early settlers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (L.D.S.), and miners. The fertile valley of Antimony has been known by several names over the years: Clover Flat[1], Grass Valley[2], Coyote[3], and after 1920, Antimony. The latest name was chosen because of the abundant antimony mines in the canyons that surround Antimony and the mining industry that the mineral supported. This valley is covered in lush grass that is naturally irrigated by Otter Creek and the East Fork of the Sevier River.

The primary native people of the valley were Southern Paiute Native Americans. Previously, approximately 10,000 years ago, early native peoples, including the Fremont and Ancestral Puebloan peoples, inhabited Southern Utah.[4] Twenty-seven miles south of Antimony, at the ranch of Jeff Rex, archaeologists found ruins known as the North Creek Shelter Site. These ruins provide insight into the lives of the native peoples that inhabited the area before European settlement. The site, used as temporary shelter by many generations of hunters and travelers, contains artifacts from the Paiutes and earlier native peoples. Artifacts found at North Creek include stone tools, farming equipment, projectiles for hunting, pottery, and other common native objects.[5] The item from the North Creek site that received the most acclaim was a wild potato; this is the earliest documented use of potatoes in North America.[6]

North Creek Shelter Site

The more recent peoples of the region are linguistic relatives of the Utes, known as the Kaiparowits Band of the Southern Paiute.[7] Shoshone bands also occupied the area. Both groups used the substance now known as antimony (a very brittle, bluish-white metallic substance),[8] which they extracted from the canyons around Grass Valley,[9] for tools and weaponry. This Southern Paiute band engaged with Europeans (Mormon settlers and the U.S. Army) during the Black Hawk War (1865–1872), and Europeans settled permanently in the region shortly thereafter. The small Southern Pauite band that lived in Grass Valley called themselves the Paw Goosawd Uhmpuhtseng or Water Clover People.[10]

The earliest Anglo-European contact with the region occurred as a result of the Spanish Trail and the John C. Fremont explorations. A trading path off the Old Spanish Trail called the Gunnison trail was used during the 1830s and 1840s. The trail split at the summit of Salt Creek in Salina Canyon. From there, the path passed through Seven Mile Canyon and Fish Lake, descended along Otter Creek, and continued along the Sevier to the Pahvant Mountains.[11] Trading caravans used this path to supply two economies: goods and slaves. The most prominent trade goods were furs, buckskin, and dried buffalo meat. In addition, the Ute people sold captured Southern Paiutes as slaves to the Spanish traders.[12] Later, in the winter of 1853–1854, Captain John C. Fremont made his fifth and final expedition to the Western territories. During this expedition, Fremont encountered harsh weather and searched for safety. After a long trip through the San Rafael Swell, Capitol Reef, and the Awapa Plateau, Fremont and his group followed Otter Creek into Grass Valley, and there found shelter and recuperated.[13] The party later continued to Parowan for further recovery. In a letter to his sister about his trials, Fremont wrote that “the Mormons saved me and mine from death and starvation.”[14]

During the Black Hawk War, Mormon settler Captain James Andrus received orders from Brigadier General Erastus Snow to conduct a reconnaissance mission throughout Southern Utah to ascertain the strength of Native American communities in the region. This group passed through Grass Valley on September 4, 1866. In Grass Valley, the soldiers found the most “extensive” defense works they had ever encountered, erected by the Southern Paiutes.[15]

Brigham Young, then president of the L.D.S. Church, organized the first Mormon exploration party into Grass Valley in 1873, following the end of the Black Hawk War. The group included Albert K. Therber, William Jex, Abraham Holladay, General William Pace, George Bean, and George Evans. Throughout Southern Utah, Chief Tabiona of the Shoshone tribe served as their guide. During their exploration of Southern Utah, on June 18, 1873, they camped at what is known today as Antimony Bench. That evening, they recorded in their journal that “We were just going to camp for the night when we saw an old coyote with three young ones. We gave chase and caught the little ones, cut their ears off short, tied a paper collar around one’s neck and turned them loose. We named the stream Coyote.”[16] Thus, Grass Valley was renamed Coyote.

In 1873, the first European settler arrived in the valley: Albert Guiser. Guiser and his family owned mines in Oregon, namely the Bonanza, the Brazos, the Pyx, and the Worley mines. He likely came to Utah as a mining speculator because of the propaganda surrounding Utah during the national mining fervor and its promised mineral riches. Guiser established a cattle operation in the valley as well, yet did not establish a permanent settlement or buildings in Coyote, only visiting during summer.[17]

To understand the account of Antimony’s first permanent settlers, one must be acquainted with the practice by the adherents of the Mormon faith known as the United Order. The United Order, established by Brigham Young, was an economic concept based on cooperative and communitarian ideals. In the Order, all property was held in common, whereby its participants’ goal was to become self-sufficient from the external world. Most United Order communities only lasted a few years before dissolving.[18] Two Order communities that had lasting effects on Antimony were Kingston and Circleville. John Rice King, son of the leader of the Order in Kingston, purchased the Antimony Guiser cattle operation as part of the Order.[19] Two prominent future leaders of Antimony came from United Order communities: Isaac Riddle and Culbert King, from Kingston and Circleville, respectively. Riddle used Grass Valley to graze the Order’s cooperative beef herd. The Order from Kingston built a dairy beside Riddle’s ranch in Antimony.[20] After the dissolution of the Order in 1878, Isaac, Culbert, and others came to Grass Valley.

Isaac Riddle was the first permanent settler in Coyote. Riddle was born in Boone County, Kentucky, where his family converted to the Mormon faith and moved to Nauvoo, Illinois. He enjoyed his time making shingles for the Nauvoo temple. Riddle spoke of the challenges that he encountered from the “mobbers of Illinois,” who persecuted the Mormons. He also described the troubles of 1844 that the Mormons encountered in Nauvoo at the murder of the founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith. Notably, he wrote a description of Smith’s death, stating that “he cannot tell how we felt.” For the next six years, while migrating to Utah, Riddle endured numerous trials. His three-year journey to Winter Quarters in Omaha resulted in his “destitute condition.” To add further challenges, Riddle’s father left him in charge of the family in Omaha for two years when he was only 17 years old. After his arrival in Utah, Brigham Young called on Riddle and Jacob Hamblin to go on a mission to Southern Utah to improve relations with the native people.[21] Riddle’s exploration of Utah resulted in his acquisition of a vast estate throughout Southern Utah. In 1875, Riddle and his son, Isaac Jr., built ranches on the east fork of the Sevier River in Grass Valley.[22] Isaac and his son had explored the area the year before and assessed it to be perfect for cattle because of its abundant water and natural meadows. In addition to Riddle, John Hunt, Joseph Hunt, Gideon Murdock, and Walter Hyatt all used Antimony for cattle grazing.[23] Riddle was a shrewd businessman. To this end, he allotted a part of his ranches as a stopover for travelers on their way to Hole-In-The-Rock.[24] Riddle’s financial interests not only included ranches, but he also established many grist mills and sawmills throughout the region. After the dissolution of the United Order, Riddle owned thousands of cattle, sheep, and horses. He was also a polygamist with multiple wives, which resulted in his incarceration, along with George Q. Cannon, an apostle of the L.D.S. Church, from September 1887 to February 1888 for polygamy under the Edmunds Tucker Act. Riddle died on September 1, 1906.

Isaac Riddle

Isaac Riddle in Prison for Polygamy with George Q. Cannon (L.D.S. Apostle) Riddle is the in the second row, first person on left side

In 1878, around the Riddle Ranch, the town of Antimony began when thirty-three Mormon families—some of whom were friends of the Riddles—moved into the valley. The most noteworthy among the settlers were the Eliza Esther McCullough, Elizabeth Ann Callister, Sarah Elizabeth Pratt, Lydia Ann Webb, and Culbert King families; the Eliza Syrett and Volney King family; the Helen Maria Webb and John King family; the Mary Theodocia Savage and John Dingman Wilcox family; the Esther Clarinda King and George Black family; the Polly Ann Ross and Culbert Levi King family; the Christina Brown and Mortimer W. Warner family; the Charles E. Rowen family; the Knute Peterson family; the Peter Neilson family; and the James Huff family.[25]

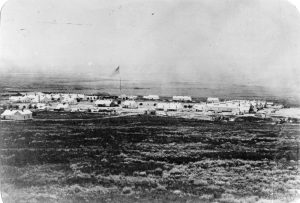

Antimony Post Office 1896

Of the first settlers in Antimony, one prominent member of the community, Culbert King, became the spiritual leader of the early Mormon settlers. King was born on January 31, 1836, in the state of New York. His parents joined the L.D.S. Church and moved to Illinois. In Nauvoo, the King family became acquainted with the religious leader, Joseph Smith. Following Smith’s murder they joined the migration of the Saints in 1846, arriving in Utah in 1851. Shortly after their arrival, Brigham Young sent the Kings to Fillmore, Millard County, where they erected the first house in the area. King served as a soldier during both the Walker and Black Hawk wars. Afterward, he became a friend to the Southern Paiutes and became somewhat proficient in speaking their language. After staying for 15 years in Kanosh, he moved to Circleville, Piute County, where he lived in the United Order for several years and served as a member of the ecclesiastical leadership there until the Order dissolved. He then relocated to Grass Valley and, in 1882, became bishop of the L.D.S. ward. From December 1885 to June 1886, he was imprisoned for polygamy. He continued to serve as bishop until 1901 when he was released and ordained a patriarch by Apostle Francis M. Lyman. He died on October 29, 1909. He and his wives were all buried in Antimony.[26]

Culbert King

Culbert King with Primary Assocation

The most prominent non-Mormon settler and early miner in Antimony was Archibald Munchie Hunter. After emigrating from Scotland to the United States through Boston in 1851, Hunter’s career took him across the nation. In 1874, he arrived in Utah and resided in Sevier County as a breeder of thoroughbred racehorses. In 1879, he joined the settlers in Antimony. That he felt at home in Antimony is no surprise, given the communitarian beliefs of the town founders and Hunter’s prominence as a socialist. He spent the rest of his life there, supporting himself by providing supplies to various mining speculations, running a hotel, and raising and exporting his horses to Scotland. The successful mining efforts of Hunter and others gave the town its current name—Antimony—after the mineral that he and others mined in the canyons above the town. When he moved to Antimony in 1879, Hunter became chairman of the school board, and residents who experienced financial difficulties testified to Hunter’s generosity. Hunter cared for his sister, Jane Talbot, and her five children in his home, which he also ran as a hotel. He died in Antimony in 1931 and was buried in Salt Lake City.[27]

Archibald M. Hunter

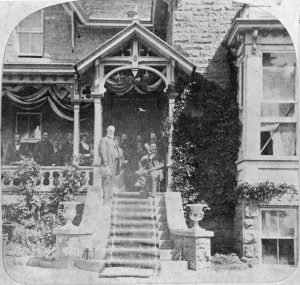

Archibald Hunter with Family in front of his hotel

Archibald, as a school board trustee and benefactor, is significant to another group of Antimony pioneers: its earliest women. Female pioneers in Antimony influenced the town substantially, most notably as teachers and nurses. Carrie Henry, Lydia Tebbs Winters, and Esther Clarinda Black were the first teachers in Coyote. In 1882, at the home of George Black, the first schoolhouse was built, and in 1885, the school found its more permanent residence in the newly built church, until a dedicated school building was built in 1916. The school’s most remembered teacher was Esther Clarinda Black. One of her students, Lillian McGillvra Abbott, remembered her as having a “pleasant disposition.”[28] Black’s daughter, Esther Black Matthews, revered her mother. She recalled that Black began to teach out of necessity to provide for her family while her husband, George Black, served a mission for the L.D.S. Church in England.[29] Black’s impact on the community cannot be understated due to her effect on the town’s children. Black served for 23 years as the town leader of the youth organization of the L.D.S. Church, named the Primary Association, thus influencing the education and spiritual lives of the town’s children.[30]

Lydia Tebbs Winters with Antimony School Children

In addition to teaching, Esther was also a midwife. Midwifery and nursing were vital to the health of the young town. The first baby born in Antimony was Forrest King, son of John R. and Helen King, on April 1, 1879.[31] Some of the most esteemed nurses were Catherine Wilcox Webb and her two daughters, Helen Matilda Webb King and Lydia Webb Huntley,[32] among whom Catherine’s history is remarkable. Her first husband was Eber Wilcox, a member of Zion’s Camp, a Mormon militia organized by Joseph Smith to reclaim property stolen from members of the faith by Missourians. Wilcox died of cholera while on the Zion’s Camp expedition at Fishing River.[33] Joseph Smith officiated over Catherine’s marriage to her second husband, John Webb, in Kirtland, Ohio.[34] Catherine and her family came to Utah as original overland pioneers with the James Pace Company in 1850[35] and settled in Fillmore. After Catherine’s husband was killed guarding the fort at Fillmore during the Black Hawk War,[36] she joined her children in Coyote. She and her daughters were excellent nurses. Upon Catherine’s death, her obituary said of her that “her sphere of usefulness was unbounded as she assisted at the birth of many and at the bedside of the sick. She knew her profession well and was extensively known and well-beloved by all her acquaintances.”[37]

Catherine Wilcox Webb

From its humble pioneer beginnings, the town now known as Antimony made its mark on the Utah history in both the 19th and 20th centuries. The infamous Butch Cassidy and his group of criminal outlaws often frequented the area when it was known as Coyote and one-time marshal George Black encountered the gang there.[38] The telephone line arrived in Antimony in 1912, permanently connecting the town to the outside world.[39] That same decade, Antimony contributed in two ways to World War I. First, it sent eight of its young men to serve: Alonzo Black, Nelo Brindley, Loril Carpenter, Glen Crabb, Wilford Davis, Gus Lambson, David Nicholes, and Arnold Smoot. All eight returned home with honorable discharges. In addition to its soldiers, two antimony mines shipped ore to ammunition plants as part of the war effort. Following the war, the global influenza pandemic claimed four of Antimony’s residents: George Jolley, Arella Smoot, Thomas Ricketts, and Nephi Black.[40]

The official incorporation of Antimony as a town occurred in 1934, during the peak of its population. The 1880 census counted the town’s population as 125, and it rose in the 1920s and 1930s to its all-time peak of 290. It then precipitously declined until it began to rise again in 2000 and is just over 130 today. In 1938, The Works Progress Administration of the New Deal brought culinary water to Antimony.[41] Its population decline over the 20th century is a result of the difficulties of farming and mining in the region. The antimony mines closed after World War I. Without mining, Antimony had to rely solely on its agriculture. Antimony has always been a farming community, with the potato as its most common crop. The former importance of potato farming is demonstrated all over Antimony today in the potato cellar derelicts that dot the highway and roads throughout town.

Antimony Potato Cellar

While World War II was raging half a world away, L.D.S. Apostle Marion G. Romney spoke at the dedication of the newly built Antimony Ward chapel on April 23, 1944. In his dedicatory prayer, Romney prayed for those from Antimony and the rest of the U.S. who were serving overseas. He said, “Bless our boys and girls in the armed services who are spread out upon the earth in this great war.”[42] Antimony sent the following young men to battle in World War II: Lark Allen, Wayne Allen, Burns Black, Noel Black, Dean Crabb, Keith Crabb, Keith Gates, Robert Gates, Dahl Gleave, Marthell Gleave, George Jolley, R.J. Jolley, Arthell King, Darral King, Eugene King, Fount Lambson, Boyd Lindquist, Verl McInelly, Alton Mathews, Dasel Mathews, Gerald Mathews, Calvin Montague, Cecil Montague, Arden Nay, Clinton Nay, Harvey Nay, Merrill Nay, Guyle Riddle, Ted Riddle, James Sandberg, Lynn Savage, LaMaun Sorenson, Harmon Steed, Robert Steed, Arther Twitchell, Clarence Twitchell, Ephrium Twitchell, Grant Warner, Robert O. Warner, Warren Wildon, Carling Young, and Verl Young. All of these men returned home, except for three who were killed in action: Lark Allen, Ted Riddle, and Arther Twitchell. On Friday, May 30, 1947, the town held a service in honor of its war veterans. It was presided over by the president of the Panguitch L.D.S. Stake, Douglas Q. Cannon, and the bishop of the L.D.S. ward, Chester Allen, who had lost his son, Lark.

Antimony War Veterans Plaque – WWI & WWII

Dedicatory Services for Bronze Plaque Program Cover

Dedicatory Services for Bronze Plaque Program Inside

In 1946, electricity arrived in Antimony. The first home in which the Garkane Power Company installed its service was that of Avera and Ivan Montague.[43] Throughout the first half of the 20th century, dances were held in one of the canyons leading out of Antimony at the Purple Haze dance hall. When it opened, for 50 cents, people from towns around Antimony came to hear the live orchestra and dance late into the night as the sunset cast a purple haze over the canyon. The dance hall closed in the 1960s as the popularity of social dancing subsided.[44]

Throughout the last half of the 20th century, Antimony’s population dwindled, even dipping below 100 residents in 1990. One reason for this was the declining potato crop industry and other farming struggles.[45] Another reason was the pull factor that drew the younger generations of Antimony into larger cities. Population decline usually has a negative economic effect on rural towns. The impact of this is evident in the median income of Antimony households dropping to $22,500 in 2010, as reported by the 2010 census. However, since its lowest population point, Antimony is rebounding, largely due to its tourism and recreational significance, as the town is on the route to Bryce Canyon, a U.S. National Park. Antimony also has the advantage of being part of the American Discovery Trail, a non-motorized trail that one can use to travel across middle America. The trail is “a new breed of national trail—part city, part small town, part forest, part mountains, part desert—all in one trail. Its 6,800+ miles of continuous, multi-use trail stretches from Cape Henlopen State Park, Delaware, to Pt. Reyes National Seashore, California.”[46] Furthermore, Mayor Shannon Allen has brought popularity to Antimony with a fireworks display every Independence Day. Antimony is home to many highly popular attractions: the Antimony Mercantile, Otter Creek Reservoir, and the Rockin’ R Ranch. The “Merc” is well-known for its half-pound Antimony Burger, the Rockin’ R for its dude ranch experience, and Otter Creek for its unprecedented trout fishing. As its citizens attest, Antimony owns a special place in Utah’s history.

References

Primary Sources

Abbott, Lillian McGilvra. My Life Story. No Date. http://utahhistoricalmarkers.org/primary-source/1693/

Deseret News (July 1884): 16.

Garfield County News (April 1923): 6.

The Engineering and Mining Journal (1896).

The Joseph Smith Papers, Journals 1 (1832–1839).

Fremont, Capt. J. C. Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon and North California in the years 1843-44. Washington: Gales and Seaton, printers, 1845. https://books.google.com/books?id=W8ICAAAAMAAJ&oe=UTF-8

King, Culbert Biographical Sketch of Culbert Levi King. No Date. http://utahhistoricalmarkers.org/primary-source/biographical-sketch-of-culbert-king/

Mathews, Esther Black. A Short Sketch of My Life: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers. 1947. http://utahhistoricalmarkers.org/primary-source/a-short-sketch-of-my-life-esther-black-mathews/

Riddle, Isaac. “Autobiography of Isaac Riddle.” In The Descendants of John Riddle, edited by Chauncey Cazier Riddle, 2003. http://utahhistoricalmarkers.org/primary-source/autobiography-of-isaac-riddle/

Utah Department of Heritage & Arts. “Archibald Murchie Hunter Papers.” No date. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=462879#idm45468671543968.

Utah Digital Newspapers. ” Salt Lake Tribune | 1885-12-13 | The Second District Court.” No date. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/details?id=13144326&page=3&facet_paper=%22Salt+Lake+Tribune%22&date_tdt=%5B1885-12-13T00%3A00%3A00.000Z+TO+1885-12-13T00%3A00%3A00.000Z%5D.

Wallace, John Hankins. Wallace’s Monthly 9 (1883).

Secondary Sources

American Discovery Trail. “INFORMATION ABOUT THE AMERICAN DISCOVERY TRAIL.” No date. https://discoverytrail.org/about/.

Biography of Catherine Narrowmore. Fillmore, Utah: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers. No Date.

Brown, Harlow F. Grass Valley History. Ogden: FamilySearch International, 1937.

Chidester, Ida, and Eleanor Bruhn. Golden Nuggets of Pioneer Days: A History of Garfield County. Panguitch, Utah: The Garfield County News, 1949.

Crampton, C. Gregory. “Military Reconnaissance in Southern Utah, 1866.” Utah Historical Quarterly 32, no. 2 (1866): 145–161.

Gottfredson, Peter, Indian Depredations in Utah. Salt Lake City: Press of Skelton Publishing Co., 1919.

Gunnerson, James H. The Fremont Culture: A Study in Culture Dynamics on the Northern Anasazi Frontier, Papers of the Peabody Museum, vol. 59, No. 2. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1920.

Janetski, Joel C., Mark L. Bodily, Bradley A. Newbold, and David T. Yoder. “Deep Human History in Escalante Valley and Southern Utah.” Utah Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (2001): 5–24.

Jensen, Andrew. Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City: Press of Skelton Publishing Co., 1941.

Kelly, Isabel T. Southern Paiute Ethnography. Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964.

Louderback, Lisbeth A., Bruce M. Pavlik “Ancient potato use in North America.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 29 (July 2017): 201705540.

Mormon Historic. “North America & Hawaii.” No date. http://mormonhistoricsites.org/zions-camp/.

Newell, Linda King, and Vivian Linford Talbot. A History of Garflied County. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1998.

Newell, Linda King. A History of Piute County. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1999.

Nielsen, Mabel Woodard, and Audrie Cuyler Ford. Johns Valley: The Way We Saw It. Springville: Art City Publishing Co., 1971.

Periodic Table of the Elements. “Antimony.” https://mineralseducationcoalition.org/elements/antimony/.

Probasco, Christian. Highway 12 – Hoodoo Lands and the Rim Red and Bryce Canyons, the Paunsaugunt Plateau. Salt Lake City: Utah State University Press, 2005.

Reeve, W. Paul, and Ardis Parshall. Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2010.

“Catherine Webb.” Overland Travel Pioneer Database, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/overlandtravel/pioneers/5927/catherine-webb.

Warner, M. Lane. Antimony, Utah – Its History and Its People 1873-2004, 2nd ed. Provo, Utah 2004.

[1] John Hankins Wallace, Wallace’s Monthly 9 (1883): 625.

[2] Andrew Jensen, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Press of Skelton Publishing Co., 1941), 4.

[3] Lane M. Warner, Antimony, Utah – Its History and Its People 1873-2004, 2nd ed. (Provo, Utah, 2004), 5.

[4] James H. Gunnerson, The Fremont Culture: A Study in Culture Dynamics on the Northern Anasazi Frontier, Papers of the Peabody Museum, vol. 59, No. 2 (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1920).

[5] Joel C., Janetski et al. “Deep Human History in Escalante Valley and Southern Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (2001): 5–24.

[6] Lisbeth A. Louderback and Pavlik M. Bruce, “Ancient potato use in North America,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 29. (July 2017): 201705540.

[7] Isabel Kelly, “Southern Paiute Ethnography,” Anthropological Papers No. 69, Glen Canyon Series No. 21 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964)

[8] Periodic Table of the Elements, “Antimony,” https://mineralseducationcoalition.org/elements/antimony/.

[9] Warner, Antimony, Utah, 4.

[10] Linda King Newell and Vivian Linford Talbot, A History of Garflied County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1998), 62.

[11] Harlow F. Brown, Grass Valley History, (Ogden: FamilySearch International, 1937), 2.

[12] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 43.

[13] Brown, Grass Valley History, 2.

[14] Capt. J. C. Fremont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon and North California in the years 1843-44 (Washington: Gales and Seaton, printers, 1845).

[15] Gregory C. Crampton, “Military Reconnaissance in Southern Utah, 1866,” Utah Historical Quarterly 32, no. 2 (1866): 159.

[16] Peter Gottfredson, Indian Depredations in Utah (Salt Lake City: Press of Skelton Publishing Co., 1919): 324-330.

[17] The Engineering and Mining Journal (1896): 383.

[18] W. Paul Reeve and Ardis Parshall, Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2010), 287.

[19] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 119.

[20] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 127.

[21] Riddle, Isaac. 2003. Autobiography of Isaac Riddle in The Descendants of John Riddle. Edited by Chauncey Cazier Riddle.

[22] Jensen, Andrew. 1941. Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Deseret News. 4.

[23] Nielsen, Mabel Woodard, and Audrie Cuyler Ford. 1971. Johns Valley: The Way We Saw It. Springville, UT: Art City Publishing Co. 196.

[24] Probasco, Christian. 2005. Highway 12 – Hoodoo Lands and the Rim Red and Bryce Canyons, the Paunsaugunt Plateau. Utah State University Press. 33.

[25] Chidester, Ida, and Eleanor Bruhn. 1949. Golden Nuggets of Pioneer Days – A History of Garfield County. Panguitch, Utah: The Garfield County News. 124.

[26] Jensen, Andrew. 1941. Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Deseret News. 185

[27] Archibald Murchie Hunter Papers, 1871-1933. MSS B 68. Utah State Historical Society Archive, Salt Lake City, Utah

[28] Mathews, Esther Black. 1947. A Short Sketch of My Life: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers.

[29] Abbott, Lillian McGillvra. My Life Story

[30] Garfield County News. 1923. April 20: 6.

[31] Linda King Newell, A History of Piute County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1999), 129.

[32] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 120.

[33] http://mormonhistoricsites.org/zions-camp/

[34] The Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, vol. 1 1832-1839.

[35] https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/overlandtravel/pioneers/5927/catherine-webb

[36] Biography of Catherine Narrowmore. Fillmore, Utah: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers.

[37] Deseret News. 1884. July 30: 16.

[38] Warner, Antimony, Utah ,96.

[39] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 222.

[40] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 258.

[41] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 294.

[42] Warner, Antimony, Utah, 71.

[43] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 300.

[44] Warner, Antimony, Utah, 77.

[45] Newell and Talbot, A History of Garflied County, 337.

[46] https://discoverytrail.org/about/

Antimony Mining Company Stock Certificate