write-up by Shannon Gebbia

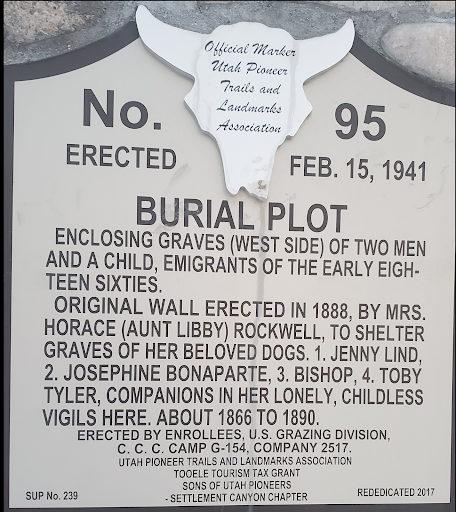

Placed by: Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Associations, No 95

GPS Coordinates: N 40° 07.123, W 112° 34.660

Historical Marker Text:

BURIAL PLOT

Enclosing graves (west side) of two men and a child emigrants of the early eighteen sixties.

Original wall erected in 1888, By Mrs. Horace (Aunt Libby) Rockwell to shelter graves of her beloved dogs. 1. Jenny Lind, 2. Josephine Bonaparte, 3. Bishop, 4. Toby Tyler, Companions in her lonely, childless vigils here about 1866 to 1890.

Erected by enrollees U.S. grazing division C.C.C camp g-154, company 2517.

Utah pioneer trails and landmarks association Tooele tourism tax grant

Sons of Utah pioneers

-settlement canyon chapter

SUP No. 239 Rededicated 2017

Extended Research:

Sometime between 1860 and 1870, Horace Rockwell and his wife Elizabeth “Libby” Rockwell moved to Skull Valley, a 40-mile long valley in what is now Tooele County, Utah. They operated the Pony Express station known as Point Lookout then continued living on the property in a log cabin built by stage workers after the station had closed.[1] They became horse and cattle ranchers and garnered a reputation as “rough frontiers folk” and “two strange characters.”[2], [3] Over time, the pair came to be known affectionately as Uncle Horace and Aunt Libby.

Uncle Horace and Aunt Libby owned one of the only sources of water along their stretch of the Overland Trail and charged travelers a fee to access it. Many riders and locals remembered Aunt Libby for smoking a pipe and treating her dogs better than her hired men.[4] Her “colony of dogs” were described as black and tan, short-haired, possibly of the “Fiste” breed (perhaps a misspelling of Feist, a small hunting terrier).[5] Aunt Libby liked to name some of her dogs after popular characters of the time, both fictional and real. Her variety of name choices reveals a wide range of interests in music, history, and popular literature: Jenny Lind, the “Swedish Nightingale” of the mid- to late-19th century opera scene; Josephine Bonaparte, the first Empress of France; and Toby Tyler, the 10-year-old protagonist of the children’s novel, Toby Tyler; or, Ten Weeks with a Circus.[6]

As testament to her devotion for her dogs, Dr. W. M. Stookey, a member of the Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks association, recalls an instance when Aunt Libby called upon Tooele’s Dr. William Bovee Dods to tend to one of her dogs, which had fallen ill. When Dr. Dods refused, Libby forced one of her workers, Elijah Perkins, to play sick, thus tricking Dods into paying a visit to the cabin. Once there, he reluctantly tended to the dog, and she paid him $100. Aunt Libby’s trick only worked once—the next time a dog got sick, the Rockwells had to travel roughly 70 miles to Salt Lake City.[7]

When one dog died en route for treatment in Salt Lake City, Aunt Libby brought him back to Point Lookout and buried him near a collection of three graves belonging to immigrants who had died while passing through Skull Valley.[8] She then hired a stone worker, Gustave E. Johnson, to build a wall around the small graveyard.[9] As her beloved dogs passed on over the years, Aunt Libby buried each one in her cemetery.

The Rockwells moved to California sometime after May 25, 1890 and lived there for the remainder of their lives.[10] Aunt Libby’s Dog Cemetery is the only structure still standing on the property known as Point Lookout.

The historical significance of this cemetery seems to be centered around its location among the Pony Express stations along Utah’s section of the Overland Trail. Unlike Horace’s brother, Orrin Porter Rockwell, Horace and Libby Rockwell were not major figures in Utah or Mormon history—monuments haven’t been built in their name, we don’t learn about them in history lessons. But one story about a rough, pipe-smoking woman who tricked a Tooele doctor into treating her sick dog has survived the test of time and given historical value to this cemetery. Dr. Stookey explains that the reason for including the cemetery as an “extra in the line, both in design and significance,” was due to a “growing increase in its unique history,” and perhaps because it is one of the only remaining structures along this section of the Overland Trail.[11] Regardless of the reasoning, by including the cemetery among Utah’s historical markers, the UPTLA created an avenue for Aunt Libby’s stories to be retold forever. Within the chasm between the details of each recollection, we find the personality of that “strange character” Aunt Libby. According to most of the people who described her over the years, she was a rough, childless, pipe-smoking woman, unafraid of outlaw Porter.[12] But by way of the legacy of pet cemetery and the stories about her dogs, we see a giving, loving, motherly woman whose cultural knowledge reached far beyond the secluded scope of the Wild West.

For Further Reference:

Primary Sources

“Fatally Burned.” Los Angeles Times. March 26, 1901. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/380059910/?terms=Mrs%2BRockwell.

Sharp Manuscript: Stories published by James P. Sharp. Compiled by Shirley Sharp Pitchford and Susan Sharp Hutchinson. Utah State Division of History Archives.

Sharp, James P. “The Pony Express Stations.” Improvement Era (February 1945): 76–77.

https://archive.org/details/improvementera4802unse/page/n21/mode/2up

Stookey, W. M. “They Died But Lived Again! Aunt Libby Rockwell’s Doggone Dogs and Their Lonely Cemetery Beside the Historic Overland.” Salt Lake Tribune. August 31, 1941. Accessed February 24, 2020. https://www.newspapers.com/image/598747615/?terms=libby%2Brockwell

Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association marker records, ca. 1930–1990s. MSS B 1457, box 1. Utah State Division of History Archives.

Secondary Sources:

Bluth, John F. “The South Central Overland Trail in Western Utah, 1850- 1900.” U. S. Bureau of Land Management. https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/101963?Reference=61466

Bluth, John F. “Supplementary Report on Pony Express Overland Stage Sites in Western Utah.” https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/101965?Reference=61468.

Fike, Richard E. and John W. Headley. “The Pony Express Stations of Utah in Historical Perspective.” Cultural Resources Series Monograph 2. Bureau of Land Management of Utah, 1979.

https://archive.org/details/ponyexpressstati00fike/mode/2up

Jessop, J. D. “The Ghost of Aunt Libby May Be Nearby.” Tooele Transcript Bulletin, October 2, 2014. http://tooeleonline.com/the-ghost-of-aunt-libby-may-be-nearby/.

[1]Bluth, John F. “The South Central Overland Trail in Western Utah, 1850-1900” (U. S. Bureau of Land Management), p. 4. (accessed February 10, 2020) https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/101963?Reference=61466; Jessop, J. D. “The Ghost of Aunt Libby May Be Nearby.” Tooele Transcript Bulletin – News in Tooele, Utah, October 2, 2014. (accessed January 29, 2020) http://tooeleonline.com/the-ghost-of-aunt-libby-may-be-nearby/; Stookey, W. M. “They Died But Lived Again! Aunt Libby Rockwell’s Doggone Dogs and Their Lonely Cemetery Beside the Historic Overland.” The Salt Lake Tribune, August 31, 1941. (accessed February 24, 2020). The exact date is unknown as several accounts differ, but they all agree the Rockwells lived at this location until sometime in 1890.

[2] Stookey.

[3] Sharp, James P., “The Pony Express Stations ,” Improvement Era, (February, 1945), 76-77. (accessed Feburay 10, 2020) https://archive.org/details/improvementera4802unse/page/n21/mode/2up

[4] Stookey.

[5] Sharp.

[6] Jessop, Stookey.

[7] Stookey, Jessop. Several newspaper stories reported this story, but the accounts differ as to which dog was ill, who called for Dods, and the amount he charged.

[8] Stookey, Bluth. Three unknown emigrating travelers died and were buried here.

[9] Stookey.

[10] Jessop; Stookey; Los Angeles Times, “Fatally Burned.” March 26, 1901. (accessed February 24, 2020) https://www.newspapers.com/image/380059910/?terms=Mrs%2BRockwell. Again, much is contested about the date, but one fact stands out: Aunt Libby burned in her house after falling asleep smoking her pipe.

[11] Stookey’s article explains the UPTLA’s haste in using the nearby CCC camps to help place markers and monuments along the difficult terrain, and that most Pony Express stations had “little or nothing remaining of the originals.” The survival of this cemetery and its story provide a picture of life along the trail.

[12]Lloyd, Erin. “Colors of Life Paint Rich Past in Rush Valley.” Tooele Transcript-Bulletin, 9 Dec. 1998, pp. 25–27. The article states Porter Rockwell owed $500 to his brother Horace, and Libby vowed to cut off Porter’s hair if the debt remained. LDS history states Porter’s hair long hair held significance to his faith. https://www.newspapers.com/image/545721374/?terms=libby%2Brockwell