Write-Up by Lindsay Adams

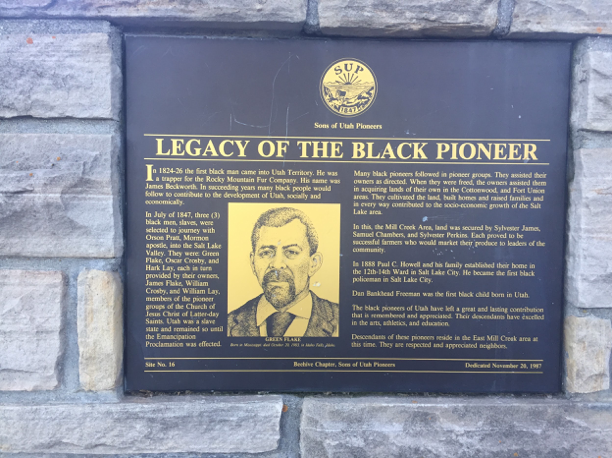

Plaque at marker for Legacy of the Black Pioneer[1]

Placed by:Beehive Chapter, Sons of Utah Pioneers and dedicated November 20, 1987.

GPS coordinates:40.6967660, -111.8272168

Historical Marker Text

In 1824-26 the first black man came into Utah Territory. He was a trapper for the rocky Mountain Fur Company. His name was James Beckwourth. In succeeding years many black people would follow to contribute to the development of Utah, socially and economically.

In July of 1847, three (3) black men, slaves, were selected to journey with Orson Pratt, Mormon apostle, into the Salt Lake Valley. They were: Green Flake, Oscar Crosby, and Hark Lay, each in turn provided by their owners, James Flake, William Crosby, and William Lay, members of the pioneer groups of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Utah was a slave state and remained so until the Emancipation Proclamation was effected.

Many black pioneers followed in pioneer groups. They assisted their owners as directed. When they were freed, the owners assisted them in acquiring lands of their own in the Cottonwood, and Fort Union areas. They cultivated the land, built homes and raised families and in every way contributed to the socio-economic growth of the Salt Lake area.

In this, the Mill Creek Area, land was secured by Sylvester James, Samuel Chambers, and Sylvester Perkins. Each proved to be successful farmers who would market their produce to leaders of the community.

In 1888 Paul C. Howell and his family established their home in the 12th-14th Ward in Salt Lake City. He became the first black policeman in Salt Lake City.

Dan Bankhead Freeman was the first black child born in Utah.

The black pioneers of Utah have left a great and lasting contribution that is remembered and appreciated. Their descendants have excelled in the arts, athletics, and education.

Descendants of these pioneers reside in the East Mill Creek area at this time. They are respected and appreciated neighbors.

Green Flake[2]

Extended Research

Between the years of 1824-26 James Beckwourth traveled with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company into what became Utah Territory. Beckwourth styled himself an explorer, fur trapper, and Indian Fighter; he was also a free man of color. Beckwourth had not always been free. Born into slavery in 1798, Beckwourth moved to Missouri with his family in 1805. In Missouri, at the age of 19 Beckwourth’s father, who was also his master, freed him from slavery. Freedom allowed Beckwourth to realize his dreams to move West as an explorer.[3]James P. Beckwourth may have been one of the first African American men to step foot into what became Utah, but he was not the last African American pioneer.

While the Legacy of the Black Pioneer plaque lists the names of three enslaved African American men (Green Flake, Oscar Crosby, and Hark Lay) who in 1847 arrived in Utah with their enslavers, it does not indicate that free men and women of color also made the trek to Utah in the same year. Notably, the year 1847 also brought the arrival of the Haight Company. This company included Jane Elizabeth Manning James, her husband Isaac, their son Silas, and Jane’s son Sylvester. Born a free woman, Mormon Missionaries converted James and her family to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1842. She was one of a handful of African American converts from Wilton, Connecticut. A year after converting, Jane and many members of her family trekked to Nauvoo, Illinois. There, in 1843 Jane became a domestic servant in the Joseph Smith household.

Arriving in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, James was a central figure in the African American Mormon community. James contributed to the building funds for temples and strongly advocated for her rights to receive ordinances and sacraments denied to her within those temples. In 1897 James was honored as one of the original Mormon Pioneers.[4]

Jane Elizabeth Manning James[5]

As Jane and Isaac demonstrate, both enslaved African Americans and free African Americans arrived in the Salt Lake valley in 1847. The historical marker also incorrectly indicates that Utah was a slave “state” until the Emancipation Proclamation. First, the Federal Government had not granted Utah statehood prior to the American Civil War. Utah gained statehood in 1896, over thirty years after the Thirteenth Amendment granted legal emancipation and banned slavery. However, Utah gained territorial status in the Compromise of 1850. This Compromise also gave Utah the ability to determine whether or not the territory would allow slavery.[6]

In 1852 the all Mormon territorial legislature answered the question of slavery when it passed “An Act in Relation to Service.” This act served as a conservative form of gradual emancipation patterned after similar bills in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. It freed no current enslaved men or women, however the act defined slaves as “servants” and implied that those born after the passage of the bill would not inherit the slave status of their parents. Although Utah’s “Servant Code” legally defined slaves as “servants,” this did not mean that men and women did not enter Utah Territory under enslavement. Some black men and women certainly entered the territory enslaved and the “Servant Code” legalized the process whereby slavery would be regulated in the territory. Interestingly, Utah’s “Servant Code” did require schooling for all servants, including those held in slavery, stating that servants must be schooled “not less than eighteen months between the ages of six years and twenty years.”[7] This was atypical for a space that allowed slavery, especially when compared to states entrenched in enslavement. For example, in 1831 North Carolina passed a law entitled “An Act To Prevent All Persons From Teaching Slaves To Read Or Write, The Use of Figures Excepted.”[8]

In allowing slavery in Utah Territory, LDS leaders sought to create a legal code that allowed converts from the South to migrate to Utah, bringing their enslaved peoples with them, some of whom had also converted to Mormonism.[9]Educating slaves prepared them for citizenship, in turn allowing them to better integrate into Utah Territory. Utah’s “Servant Code” thus legalized slavery in Utah Territory, and lasted from 1852 – 1862, when the federal government abolished slavery in all territories. However, Utah was never a slave state, and Utah’s laws surrounding slavery functioned differently than those in Southern slave states.

In 1850 the census recorded fifty African Americans within Utah Territory, twenty four of whom were enslaved, twenty six of whom were free. In 1860 the total number of African Americans had only risen to fifty nine. Over time, however, the African American population continued to grow. In 1870 Utah had an African American population of 137, and forty years later, in 1910, that number had grown to 1,144.[10]The railroad provided one source of jobs which attracted many newly freed African Americans to Utah, and Utah became home to a flourishing African American community, both LDS and non-LDS. Early black settlers provided Utah with two African American run newspapers, The Broad Ax and the Utah Plain Dealer.

Mill Creek, where this particular historical marker resides, is a wonderful example of African American community and life in Utah. Called “The Hill” by the black community, African Americans lived and farmed in Mill Creek, and the area quickly became a center for black life in the Salt Lake Valley. Some of these families, like the family of Samuel Davidson Chambers had converted to Mormonism during the period of their enslavement. After freedom came in 1865 Samuel sharecropped and cobbled shoes until he earned enough money for his family to “gather” in Utah Territory.[11] Others, like Ned Leggroan and his family, moved to Utah Territory with extended kin and sought better opportunities outside of the South. The Chambers and Leggroan family were the first black farmers in Mill Creek. Samuel Davidson Chambers purchased property in Mill Creek in 1875, with Ned Leggroan purchasing land in 1889.[12] Black families on “The Hill” farmed fruit and vegetables, and made extra money through produce and the butchering of animals. The families lived on land which now makes up Evergreen Avenue in Mill Creek. By most oral accounts African American families lived next to white families and the community was generally inclusive.[13]Descendants of African American pioneers lived and farmed in Mill Creek until the middle of the twentieth century. By this time many families had moved elsewhere in the Salt Lake Valley in search of jobs and economic opportunities outside of farming.

By 2010 the African American population in Utah had expanded to 29,287.[14]African American communities continue to be an integral part of the Utah experience.

For Further Reference

Primary Sources

“An Act to Establish Territorial Government in Utah,” September 9, 1850.

“An Act in Relation to Service,” Territorial Legislative Records, 1851-1894, series 3150, microfilm, reel 1, box 1, folder 55, pages 704-706, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City Utah.

Raleigh,”Act Passed by the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina at the Session of 1830—1831,” 1831.

Secondary Sources

Bonner, T. D. The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, and Pioneer (London: Sampson Lo Son and Co, 1856)

Bringhurst, Newell G. “The Mormons and Slavery: A Closer Look,”Pacific Historical Review, Vol 50, No. 3 (1981): 332

Johnson Karen A. “Undaunted Courage and Faith: The Lives of Three Black Women in the West and Hawaii in the Early 19th Century,” The Journal of African American History91, no. 1 (2006): 4-22

Newell, Quincy D. Your Sister in the Gospel: The Life of Jane Manning James, a Nineteenth-Century Black Mormon. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Perlich, Pamela S. “Utah Minorities: The Story Told by 150 Years of Census Data,” Bureau of Economic and Business Research, David S. Eccles School of Business, University of Utah (2002), 11.

Reiter, Tonya. “Life on the Hill: The Black Farming Families of Mill Creek.” Journal of Mormon History 44No. 4 (October 2018): 68-89

Rich, Christopher B. “The True Policy for Utah: Servitude, Slavery , and ‘An Act in Relation to Service,” Utah Historical Quarterly80 (Winter 2012) 54-74

[1]Photo taken and owned by author.

[2]“Fifty Years Ago Today.” Salt Lake Tribune, 31 May 1897.

[3]T. D. Bonner, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, and Pioneer (London: Sampson Lo Son and Co, 1856) 10.

[4]Karen A. Johnson, “Undaunted Courage and Faith: The Lives of Three Black Women in the West and Hawaii in the Early 19th Century,” The Journal of African American History91, no. 1 (2006): 4-22

[5]Miscellaneous Portraits, Circa 1862-1873. PH 5962, box 1, folder 25, image 37. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Viewable online at Century of Black Mormons

[6]“An Act to Establish Territorial Government in Utah,” September 9, 1850.

[7]Utah, “An Act in Relation to Service,” February 4, 1852.

[8]Raleigh, “Act Passed by the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina at the Session of 1830—1831,” 1831.

[9]Newell G. Bringhurst, “The Mormons and Slavery: A Closer Look,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol 50, No. 3 (1981): 332.

[10]Pamela S. Perlich, “Utah Minorities: The Story Told by 150 Years of Census Data,” Bureau of Economic and Business Research, David S. Eccles School of Business, University of Utah (2002), 11.

[11]Tonya Reiter,“Life on the Hill: The Black Farming Families of Mill Creek.” Journal of Mormon History 44No. 4 (October 2018): 70.

[12]Reiter, 73.

[13]Reiter, 88.

[14]Utah Census Viewer. Population of Utah, Census 2010 and 2000: Interactive Map.